A Very Fast Car:

Tracy Chapman and the American Imagination

Words: Plum Luard

February 23, 2024

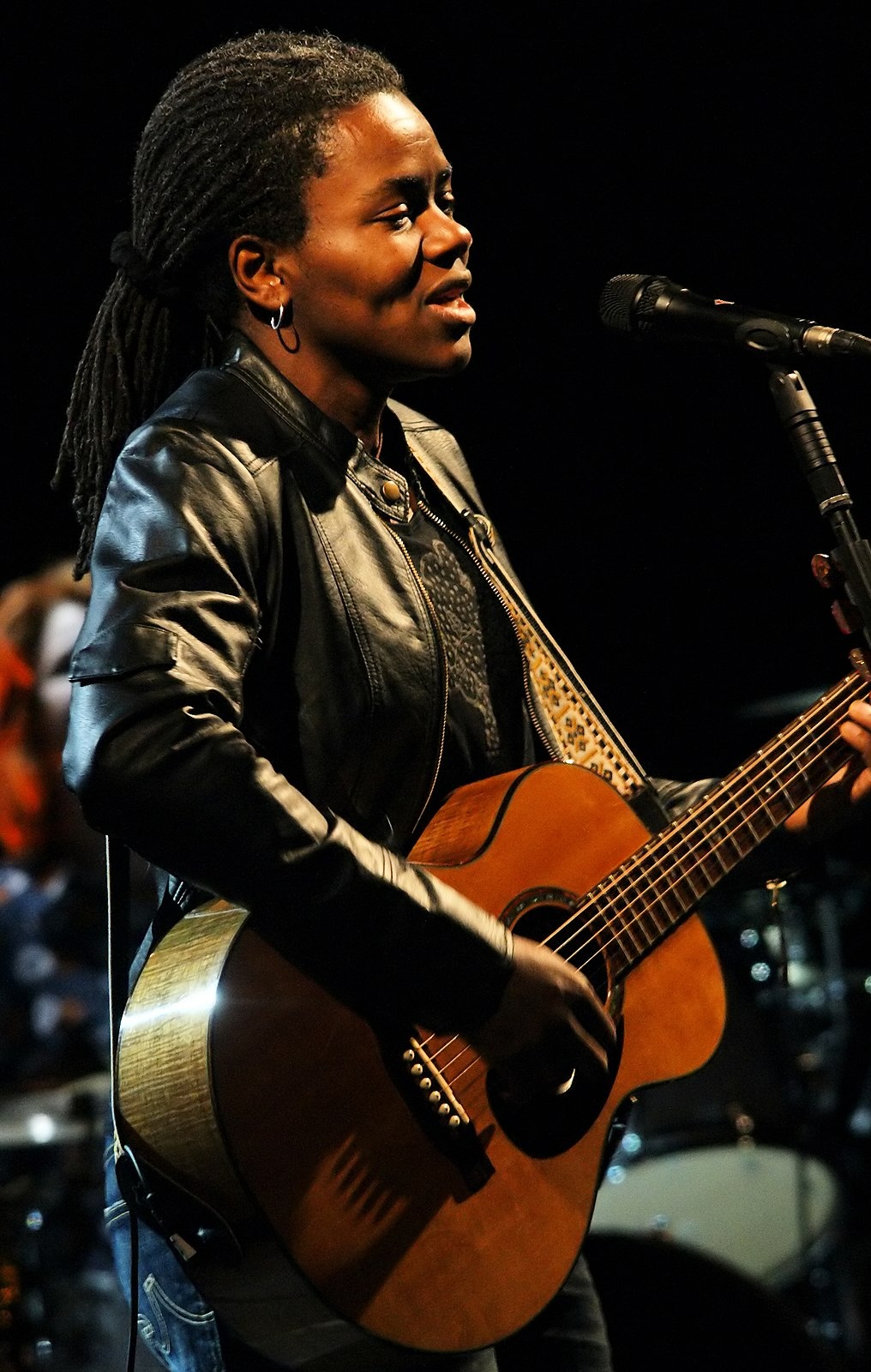

Tracy Chapman is a beloved Black singer-songwriter from Cleveland. Her mother bought her a ukulele when she was 3 years old, and she began playing guitar and writing songs when she was 8. Her household rang with the voices of Betty Wright, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Marvin Gaye and the gospel singers Mahalia Jackson and Shirley Caesar. When Tracy was growing up, Cleveland was integrating schools and implemented a busing system. She got a scholarship to a private boarding school in Connecticut and then went to Tufts for college, where everyone on campus knew her. She was always playing coffee houses. And going to Harvard Square to busk. After graduating, Chapman was signed with Elektra Records, a label that was crucial to the growth of folk and rock music at the end of the 20th century. Her namesake album was an immediate smash success. She has since won four Grammys.

Liliana and I walked home late one night and talked about how much we love Tracy. We were stomping back from the train on one of those dark, endless nights. And we talked about “Fast Car.” It was cold and we were tired and had spent the night listening to Zadie Smith and slicing old fruit with Anna’s samurai sword. We talked about fast cars and Hunter Thompson and driver’s licenses and this strange adoration we have of highways. Heat sucking and gas stained and glass strewn. Why is it all so romantic? Why do we both love Jack Keroac and his tales of sex in motel rooms and whipping wind and peeing off the back of pickups? “Fast Car” is one of those songs you feel in your bones. Shivering. It is a song about freedom. And what it would mean for something to change desperately and dramatically. And the chance to be someone. And what it feels like to sit in a car with you. Is it fast enough so we can fly away?

The trope of a fast car haunts the American imagination. A familiar image at the end of a movie. The packed car driving off into the sunset. The couple speeding off the edge of a cliff. The idea that everything you ever needed could be loaded into the trunk or strapped precariously to the top and you could just run away. It is about escape. It is about the possibility of a new life. This trope especially finds home in the white authors Jack Keuroac and Hunter Thompson, men who wrote about their reckless journeys in the American West, getting hopped up on drugs and driving as fast as the car would let them, hitching a ride with whomever was willing and talking to a stranger for hours. The 1998 trailer for the remake of Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas opens, “I advise you to rent a very fast car with no top,” and then come the screeching tires of his 1972 Chevrolet Caprice convertible.

Tracy Chapman has given the trope of a “fast car” a whole new name and a whole new home in the mouth of a Black artist. Daphne Brooks opens her book Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound with “Quiet as it’s kept, Black women of sound have a secret. Theirs is a history unfolding on other frequencies while the world adores them and yet mishears them, celebrates them and yet ignores them, heralds them and simultaneously devalues them. Theirs is a history that is, nonetheless, populated with revolutionaries.” A collection of essays, “Interrogating Boundaries,” considers different borders and boundaries from the lens of media studies, psychology, and international affairs. The introduction describes how our conceptions of technology and humanity ellide—muddying our sense of both. Humans drive technological change and yet are unable to fully stomach it, or to entirely understand it, or to conceive of it as our own. That this is a creation of our own hands. And yet, it can best us. White America pushes aside the contributions of Black female artists to sonic futures, burying them in the annals of history. They sing themselves out of the depths. The voice granted through music takes on this profound and exponential power. Lyrics and their twisting and dancing melodies pound themselves into our bodies. Black women navigate a world which denies their humanity, which tugs at their hair and targets their skin. These women sing in a voice ripe with emotion and desire and love and invite the listeners to join in it. They push through the emotive dam. And the water rushes with frightening ferocity. Black female voices “shake heaven and Earth” as Brooks notes when speaking of René Marie’s song “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” Brooks also speaks of unlocking the “felt world” through sound. And music allows us to embody just that—the world that breathes, that beats, that is alive.

Brooks continues that Black woman’s performances are revolutionary because they project Black vitality and livelihood. Chapman’s “Fast Car” proves as a perfect example of exactly this. Maybe we’ll make something. Me, myself, I got nothing to prove. Black women musicians refuse the labels ascribed to their bodies, they instead, as Brook writes, “choose to design their own mischievous and colorful, sometimes brooding and rage-filled, and always disruptive and questing definitions of a self that is intent on living a free life.” The creation of a “self” emerges as part of the fast car trope in the white American beatnik myth. Kerouac and Thompson both fight for a sense of self, ironically, in the destruction of their drug drowned bodies. And then printing their stories. Chapman doubles down on the assertion of self—me, myself.

Brook also speaks about the creation of memory in Black music. The Rolling Stone writes that “the 11 songs on Tracy Chapman are as undiluted as they could be. The production is subtle and streamlined, focused unyieldingly on Chapman’s acoustic guitar, her bluesy voice and her carefully wrought tales of characters in contemporary America who seek meaning in the face of society’s fragmentation.” Chapman’s work is a chronicle of tales and explodes the narratives of the untold. As Brook puts it, Black female artists, “stood in for and as the memory of a people.” Chapman sings in “Behind the Wall” of hearing the shouts of a woman whose husband is beating her. It will do no good to call / The police always come late. Or, “Material World”—which opens, Are own ancestors / Are hungry ghosts / Closets so full of bones / They won’t close—drags stories out of these bursting closets.

Chapman sings stories of Black women and marks them down forever in history, in a world that erases and denies these narratives.

Chapman was once asked if she considered herself a folksinger. And she was hesitant in her response, “‘I think what comes to people’s minds is the Anglo-American tradition of the folk singer, and they don’t think about the black roots of folk music. So in that sense, no, I don’t. My influences and my background are different. In some ways, it’s a combination of the black and white folk traditions.’” Jana is trying to get into folk music. “It’s happy but still emotional,” she relayed while adding Chapman to her favorite playlist.

Black folk musicians are taking back their genre. In 2022, Tray Wellington released the album “Black Banjo,” reclaiming the banjo from the white folk tradition that obscures the Black historical roots of the genre. The banjo is often associated with a white bluegrass tradition, although the origins of the instrument are found in the African tradition, in instruments such as the akonting. In the 19th century, the banjo was tied to minstrelsy. Hannah Mayree founded the Black Banjo Reclamation Project, which provides Black musicians with instruments and teaches them how to make a banjo for themselves. Other musician-folklorists are digging up source material that demonstrates the long tradition of Black folk music in America. The New York Times writes of folk music: it is a “multiracial, working-class tradition, stretching across time and continents. In the United States alone, it comprises a repertoire of ballads and work songs, blues and breakdowns, songs of love and songs of protest.” During times where people seeked to hold onto shared cultural heritage such as the Great Depression or the Red Scare, they turned to folk music. Folk is the music of the people. However, in marketing the music, the genre became incredibly segregated. With the advent of recording technology in the 1920s, music executives and most famously Ralph Peer of Okeh Records, created a genre defined by racialized distinctions. So-called race records were marketed for Black Americans and hillbilly records for southern white Americans. Producers often solicited only protest songs and lamenting ballads from Black artists rather than uplifting songs of joy. More genres that were racially coded emerged, such as R&B and Soul. Folk music and a new generation of white folk artists such as Seeger, Joan Baez, Woody Guthrie, and Bob Dylan solidified the genre in American memory as white.

Chapman is a popular totem among Brown University students, especially queer students. And Chapman’s voice seems to be of particular interest. I once brought her up in a WBRU meeting where Laurie, wrapped up in a scarf blurted out, “I love her gay ass voice.” Georgia once told me that, “I until recently didn’t know if Tracy Chapman was a woman or not.”

Laurie explained what it meant to love her “gay ass voice.” She told me, “But yeah no I deeply love Tracy Chapman's voice…Just in the way that it is so particularly masculine in a still … womanly way? Like. I’ve never heard anything more androgynous and that just always fascinated me. I think… I don't know… for queer people especially, Tracy Chapman's voice is so damn comforting because it is so full and rich and unique in its … inability to be ascribed to a gender??? I hope you get what I mean. Tracy Chapman is the voice of the genderless.” And Georgia explained, “The first time I heard Tracy Chapman’s voice I was very young and I feel like there is both an androgynous quality to her voice and to her name. I think Tracy could go either way in terms of gender. And I also think there is just like a deep—there's like a deepness to her voice. That is, I guess not, like, explicitly related to gender but was like how I read it for the first time when I was a small child. And I think in the songs I was listening to it was not necessarily really clear that like the role that she was playing in the narrative of the songs was like feminine maybe.”

NPR’s Talking While Female, opens with the insulting categorizations ascribed to female voices, “Did anybody ever tell you you have kinda a child-like voice?” “Oh God, your voice is so annoying, it’s so squeaky, it’s so high.” “Frantic, grating, obnoxious.” “Take a shot of whisky that may help your voice sound more rich.” “If a woman’s voice is not authoritative people will not believe her.” The register of a woman’s voice is determined roughly by how tall they are and how many hormones they have. Lower pitched voices are believed to be more competent. Some female candidates, Margaret Thatcher famously, have been coached to lower their voices. Chapman finds her power in this voice that is not “girly” enough. In a voice that is hard to totally place. In a voice that projects competence in its ambiguity.

Chapman’s voice is “so soft it is barely audible,” according to the Rolling Stone. And she wields it in a way that shakes you to the core. Her debut album, Tracy Chapman, begins with “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution.” The song resounds with a fragile open strum. Don’t you know / They’re talking about a revolution? / It sounds like a whisper. The talk of revolution is quiet. And no less powerful.

The trope of a fast car haunts the American imagination. A familiar image at the end of a movie. The packed car driving off into the sunset. The couple speeding off the edge of a cliff. The idea that everything you ever needed could be loaded into the trunk or strapped precariously to the top and you could just run away. It is about escape. It is about the possibility of a new life. This trope especially finds home in the white authors Jack Keuroac and Hunter Thompson, men who wrote about their reckless journeys in the American West, getting hopped up on drugs and driving as fast as the car would let them, hitching a ride with whomever was willing and talking to a stranger for hours. The 1998 trailer for the remake of Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas opens, “I advise you to rent a very fast car with no top,” and then come the screeching tires of his 1972 Chevrolet Caprice convertible.

Tracy Chapman has given the trope of a “fast car” a whole new name and a whole new home in the mouth of a Black artist. Daphne Brooks opens her book Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound with “Quiet as it’s kept, Black women of sound have a secret. Theirs is a history unfolding on other frequencies while the world adores them and yet mishears them, celebrates them and yet ignores them, heralds them and simultaneously devalues them. Theirs is a history that is, nonetheless, populated with revolutionaries.” A collection of essays, “Interrogating Boundaries,” considers different borders and boundaries from the lens of media studies, psychology, and international affairs. The introduction describes how our conceptions of technology and humanity ellide—muddying our sense of both. Humans drive technological change and yet are unable to fully stomach it, or to entirely understand it, or to conceive of it as our own. That this is a creation of our own hands. And yet, it can best us. White America pushes aside the contributions of Black female artists to sonic futures, burying them in the annals of history. They sing themselves out of the depths. The voice granted through music takes on this profound and exponential power. Lyrics and their twisting and dancing melodies pound themselves into our bodies. Black women navigate a world which denies their humanity, which tugs at their hair and targets their skin. These women sing in a voice ripe with emotion and desire and love and invite the listeners to join in it. They push through the emotive dam. And the water rushes with frightening ferocity. Black female voices “shake heaven and Earth” as Brooks notes when speaking of René Marie’s song “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” Brooks also speaks of unlocking the “felt world” through sound. And music allows us to embody just that—the world that breathes, that beats, that is alive.

Brooks continues that Black woman’s performances are revolutionary because they project Black vitality and livelihood. Chapman’s “Fast Car” proves as a perfect example of exactly this. Maybe we’ll make something. Me, myself, I got nothing to prove. Black women musicians refuse the labels ascribed to their bodies, they instead, as Brook writes, “choose to design their own mischievous and colorful, sometimes brooding and rage-filled, and always disruptive and questing definitions of a self that is intent on living a free life.” The creation of a “self” emerges as part of the fast car trope in the white American beatnik myth. Kerouac and Thompson both fight for a sense of self, ironically, in the destruction of their drug drowned bodies. And then printing their stories. Chapman doubles down on the assertion of self—me, myself.

Brook also speaks about the creation of memory in Black music. The Rolling Stone writes that “the 11 songs on Tracy Chapman are as undiluted as they could be. The production is subtle and streamlined, focused unyieldingly on Chapman’s acoustic guitar, her bluesy voice and her carefully wrought tales of characters in contemporary America who seek meaning in the face of society’s fragmentation.” Chapman’s work is a chronicle of tales and explodes the narratives of the untold. As Brook puts it, Black female artists, “stood in for and as the memory of a people.” Chapman sings in “Behind the Wall” of hearing the shouts of a woman whose husband is beating her. It will do no good to call / The police always come late. Or, “Material World”—which opens, Are own ancestors / Are hungry ghosts / Closets so full of bones / They won’t close—drags stories out of these bursting closets.

Chapman sings stories of Black women and marks them down forever in history, in a world that erases and denies these narratives.

Chapman was once asked if she considered herself a folksinger. And she was hesitant in her response, “‘I think what comes to people’s minds is the Anglo-American tradition of the folk singer, and they don’t think about the black roots of folk music. So in that sense, no, I don’t. My influences and my background are different. In some ways, it’s a combination of the black and white folk traditions.’” Jana is trying to get into folk music. “It’s happy but still emotional,” she relayed while adding Chapman to her favorite playlist.

Black folk musicians are taking back their genre. In 2022, Tray Wellington released the album “Black Banjo,” reclaiming the banjo from the white folk tradition that obscures the Black historical roots of the genre. The banjo is often associated with a white bluegrass tradition, although the origins of the instrument are found in the African tradition, in instruments such as the akonting. In the 19th century, the banjo was tied to minstrelsy. Hannah Mayree founded the Black Banjo Reclamation Project, which provides Black musicians with instruments and teaches them how to make a banjo for themselves. Other musician-folklorists are digging up source material that demonstrates the long tradition of Black folk music in America. The New York Times writes of folk music: it is a “multiracial, working-class tradition, stretching across time and continents. In the United States alone, it comprises a repertoire of ballads and work songs, blues and breakdowns, songs of love and songs of protest.” During times where people seeked to hold onto shared cultural heritage such as the Great Depression or the Red Scare, they turned to folk music. Folk is the music of the people. However, in marketing the music, the genre became incredibly segregated. With the advent of recording technology in the 1920s, music executives and most famously Ralph Peer of Okeh Records, created a genre defined by racialized distinctions. So-called race records were marketed for Black Americans and hillbilly records for southern white Americans. Producers often solicited only protest songs and lamenting ballads from Black artists rather than uplifting songs of joy. More genres that were racially coded emerged, such as R&B and Soul. Folk music and a new generation of white folk artists such as Seeger, Joan Baez, Woody Guthrie, and Bob Dylan solidified the genre in American memory as white.

Chapman is a popular totem among Brown University students, especially queer students. And Chapman’s voice seems to be of particular interest. I once brought her up in a WBRU meeting where Laurie, wrapped up in a scarf blurted out, “I love her gay ass voice.” Georgia once told me that, “I until recently didn’t know if Tracy Chapman was a woman or not.”

Laurie explained what it meant to love her “gay ass voice.” She told me, “But yeah no I deeply love Tracy Chapman's voice…Just in the way that it is so particularly masculine in a still … womanly way? Like. I’ve never heard anything more androgynous and that just always fascinated me. I think… I don't know… for queer people especially, Tracy Chapman's voice is so damn comforting because it is so full and rich and unique in its … inability to be ascribed to a gender??? I hope you get what I mean. Tracy Chapman is the voice of the genderless.” And Georgia explained, “The first time I heard Tracy Chapman’s voice I was very young and I feel like there is both an androgynous quality to her voice and to her name. I think Tracy could go either way in terms of gender. And I also think there is just like a deep—there's like a deepness to her voice. That is, I guess not, like, explicitly related to gender but was like how I read it for the first time when I was a small child. And I think in the songs I was listening to it was not necessarily really clear that like the role that she was playing in the narrative of the songs was like feminine maybe.”

NPR’s Talking While Female, opens with the insulting categorizations ascribed to female voices, “Did anybody ever tell you you have kinda a child-like voice?” “Oh God, your voice is so annoying, it’s so squeaky, it’s so high.” “Frantic, grating, obnoxious.” “Take a shot of whisky that may help your voice sound more rich.” “If a woman’s voice is not authoritative people will not believe her.” The register of a woman’s voice is determined roughly by how tall they are and how many hormones they have. Lower pitched voices are believed to be more competent. Some female candidates, Margaret Thatcher famously, have been coached to lower their voices. Chapman finds her power in this voice that is not “girly” enough. In a voice that is hard to totally place. In a voice that projects competence in its ambiguity.

Chapman’s voice is “so soft it is barely audible,” according to the Rolling Stone. And she wields it in a way that shakes you to the core. Her debut album, Tracy Chapman, begins with “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution.” The song resounds with a fragile open strum. Don’t you know / They’re talking about a revolution? / It sounds like a whisper. The talk of revolution is quiet. And no less powerful.