Revolutionary Roots:

Listening to Black Artists

Words: Sophie Culpepper

August 16 2020

Can art be a form of activism? How can art reimagine a more inclusive, equitable future?

This article engages with Black artists to listen to and center the stories they wish to tell about their lived experiences, art practices, and how they challenge norms of identity, beauty, and history.

We use spotlighted audio segments and longer pieces drawn from interviews with each artist which are published on an ongoing basis. Through these interviews, we highlight some of the myriad intersections of art and activism in various Black artistic practices present in personal and shared narratives about ongoing creations and critiques.

We use spotlighted audio segments and longer pieces drawn from interviews with each artist which are published on an ongoing basis. Through these interviews, we highlight some of the myriad intersections of art and activism in various Black artistic practices present in personal and shared narratives about ongoing creations and critiques.

For artist Jordan Seaberry, painting is not only a way to tell stories: The art form “actually builds power.” Painting magnifies historically neglected African-American memory and empowers community in the work of Seaberry, who is a grassroots organizer for criminal justice reform and drug policy reform specifically.

His art and organizing inform each other, because “imagination is the bedrock of social change.” It it his hope that his “painted work is able to live alongside “his) political work, and that those two threads can weave back and forth.”

Originally from the South Side of Chicago, where his grandfather moved during the Great Migration, Seaberry came to Providence to attend the Rhode Island School of Design, his “dream school.” But at school, he “really struggled to feel at home” and dropped out — thinking he would never return. Seaberry took a step back from art, and threw himself into community organizing instead — where he “built a network and bonds and routes that I cherish to this day, folks that I still consider my family in many cases.” After a few years, Seaberry realized he owed it to his newly established community to return to his art, so he returned to painting, “and loved every second of it.”

In addition to previous work as Director of Public Policy and Advocacy at the Nonviolence Institute, Seaberry now serves as the co-director of the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture — a nonprofit which is not affiliated with the government — as well as both a Protect Families First and New Urban Arts in Providence Board Member.

![]()

Originally from the South Side of Chicago, where his grandfather moved during the Great Migration, Seaberry came to Providence to attend the Rhode Island School of Design, his “dream school.” But at school, he “really struggled to feel at home” and dropped out — thinking he would never return. Seaberry took a step back from art, and threw himself into community organizing instead — where he “built a network and bonds and routes that I cherish to this day, folks that I still consider my family in many cases.” After a few years, Seaberry realized he owed it to his newly established community to return to his art, so he returned to painting, “and loved every second of it.”

In addition to previous work as Director of Public Policy and Advocacy at the Nonviolence Institute, Seaberry now serves as the co-director of the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture — a nonprofit which is not affiliated with the government — as well as both a Protect Families First and New Urban Arts in Providence Board Member.

Find out more about Jordan Seaberry and his work here︎︎︎

To support the Nonviolence Institute, learn more here︎︎︎

Casandra Inez and Spocka Summa first met in high school over 15 years ago. Casandra, whose family is Guatemalan, is an educator, poet, organizer and founder of the annual “On the Lawn” festival; Spocka is a visual artist, musician,event manager, curator and “overall a creative individual” with Nigerian roots.

Both artist-entrepreneurs were born and raised in Providence, and they have dedicated themselves to providing creative opportunities to the Providence community.

Cas recalled consuming and creating art “from when I was very young” but “didn’t come from a creative family. So I always felt like that stuck out from where I’m from.” She performed spoken word poetry for the first time as a junior in her high school cafeteria. “It lasted about three or four minutes, and it felt like the longest performance ever,” she remembered. She has continued since to experiment with storytelling in various forms, from photography to screen printing to digital art and videography. But Cas also always returns to working directly with language: She thinks of poetry as “something you can do wherever you are” and something that is accessible to everyone, even those who don’t think of themselves as consumers of art.

Spocka is currently working on a comic book called the Live Wire, which describes a system of governments and other power players “trying to assimilate (the protagonist) and, you know, turn him to be like everyone else.” The comic book, inspired “100%” by Spocka’s own experience as an artist and as a person, describes “a battle between finding yourself, staying yourself, but also not giving into the systems that are trying to change you.” He explained that he uses the image of wires because “it’s very twisted and complicated to navigate and, you know, survive through.”

Cas recalled consuming and creating art “from when I was very young” but “didn’t come from a creative family. So I always felt like that stuck out from where I’m from.” She performed spoken word poetry for the first time as a junior in her high school cafeteria. “It lasted about three or four minutes, and it felt like the longest performance ever,” she remembered. She has continued since to experiment with storytelling in various forms, from photography to screen printing to digital art and videography. But Cas also always returns to working directly with language: She thinks of poetry as “something you can do wherever you are” and something that is accessible to everyone, even those who don’t think of themselves as consumers of art.

Spocka is currently working on a comic book called the Live Wire, which describes a system of governments and other power players “trying to assimilate (the protagonist) and, you know, turn him to be like everyone else.” The comic book, inspired “100%” by Spocka’s own experience as an artist and as a person, describes “a battle between finding yourself, staying yourself, but also not giving into the systems that are trying to change you.” He explained that he uses the image of wires because “it’s very twisted and complicated to navigate and, you know, survive through.”

In early September of 2019, the two artists opened Public Shop & Gallery together, with the goal of providing space and support for local emerging BIPOC artists and consumers of art. “The idea of Public came about because we wanted to find a way to better represent the brown and Black people that are artists as well and we didn’t find that too often in our community,” Spocka explained. Cas added that “‘Oh, well I don’t have the money so I can’t do art’ -— like, that shouldn’t even be a question. If you’re an artist, alright, let’s find a way to make this happen for you.”

![]()

Public has hosted a range of events and a number of artists: 85 creators of art in their shop, 50 artists in their gallery, 12 muralists, and 8 authors in their book corner, according to their website. Cas added that Public is built on “the idea that this belongs to you too, that this is your space.”

While they had to close Public in mid-March due to COVID-19, Cas and Spocka will be moving to a new space next spring, and hope to stay in Olneyville. Their goal is to raise $16,000 by August 31st: “Running a business ain’t free. Creating art ain’t free. Supplies and labor ain’t free.”

Public has hosted a range of events and a number of artists: 85 creators of art in their shop, 50 artists in their gallery, 12 muralists, and 8 authors in their book corner, according to their website. Cas added that Public is built on “the idea that this belongs to you too, that this is your space.”

While they had to close Public in mid-March due to COVID-19, Cas and Spocka will be moving to a new space next spring, and hope to stay in Olneyville. Their goal is to raise $16,000 by August 31st: “Running a business ain’t free. Creating art ain’t free. Supplies and labor ain’t free.”

Learn more about Public and support Cas and Spocka’s “This Ain’t Free” fundraiser for their new space here︎︎︎

Artist Liz Morgan introduces herself first as “a Black woman living in the Bronx.”

The work that she does spans organizations and roles: She is “a theatre maker, a playwright, an actor, a Theatre of the Oppressed facilitator and Practitioner.” But after describing her art, Morgan adds one more identifier – she describes her hair. “Fairly short, naturally styled… Kind of in a mohawk.”

Morgan’s identity as a Black woman is fundamentally ingrained in the work that she does and the many hats she wears. She writes characters into being who are allowed to be different from one moment to another, who represent “all of the things that Black women can be.” Her writing led her to create Drammy-Award-nominated The Clark Doll, which centers around three women who “try desperately to discover what game will give them the sweetest dreams” as a metaphor for seeking joy in America as a Black woman. She is also widely recognized for her poem featured in the Huffington Post: “Why I was Late Today and Will Probably Always be Late as a Black Woman.”

Beyond her own productions, Morgan acts as both ‘Joker’ and Community Resources Coordinator for Theatre of the Oppressed NYC. Founded in 2011, the group seeks to advocate for and encourage social change by engaging in communities. They engage in “a rehearsal for real life, a rehearsal for the revolution,” Morgan explains. The organization engages in two different types of theatre: forum theatre and legislative theatre. The first practice incorporates the audience as a participant, or Spect-Actor, so that they are galvanized to consider forms of systemic oppression and possible strategies for change. In this style of theater, the versatile Joker facilitates audience engagement.

The Joker, Morgan says, is “some type of wild card that actually has to be able to play multiple hats and could really change the way things go.” So, Morgan directs, acts as a caretaker, and pushes the audience to think harder about what they are experiencing and realizing throughout the production. Legislative theatre is similarly action-oriented, and is geared specifically toward an audience including legislators, to the end of encouraging better policy solutions.

Morgan’s identity as a Black woman is fundamentally ingrained in the work that she does and the many hats she wears. She writes characters into being who are allowed to be different from one moment to another, who represent “all of the things that Black women can be.” Her writing led her to create Drammy-Award-nominated The Clark Doll, which centers around three women who “try desperately to discover what game will give them the sweetest dreams” as a metaphor for seeking joy in America as a Black woman. She is also widely recognized for her poem featured in the Huffington Post: “Why I was Late Today and Will Probably Always be Late as a Black Woman.”

Beyond her own productions, Morgan acts as both ‘Joker’ and Community Resources Coordinator for Theatre of the Oppressed NYC. Founded in 2011, the group seeks to advocate for and encourage social change by engaging in communities. They engage in “a rehearsal for real life, a rehearsal for the revolution,” Morgan explains. The organization engages in two different types of theatre: forum theatre and legislative theatre. The first practice incorporates the audience as a participant, or Spect-Actor, so that they are galvanized to consider forms of systemic oppression and possible strategies for change. In this style of theater, the versatile Joker facilitates audience engagement.

The Joker, Morgan says, is “some type of wild card that actually has to be able to play multiple hats and could really change the way things go.” So, Morgan directs, acts as a caretaker, and pushes the audience to think harder about what they are experiencing and realizing throughout the production. Legislative theatre is similarly action-oriented, and is geared specifically toward an audience including legislators, to the end of encouraging better policy solutions.

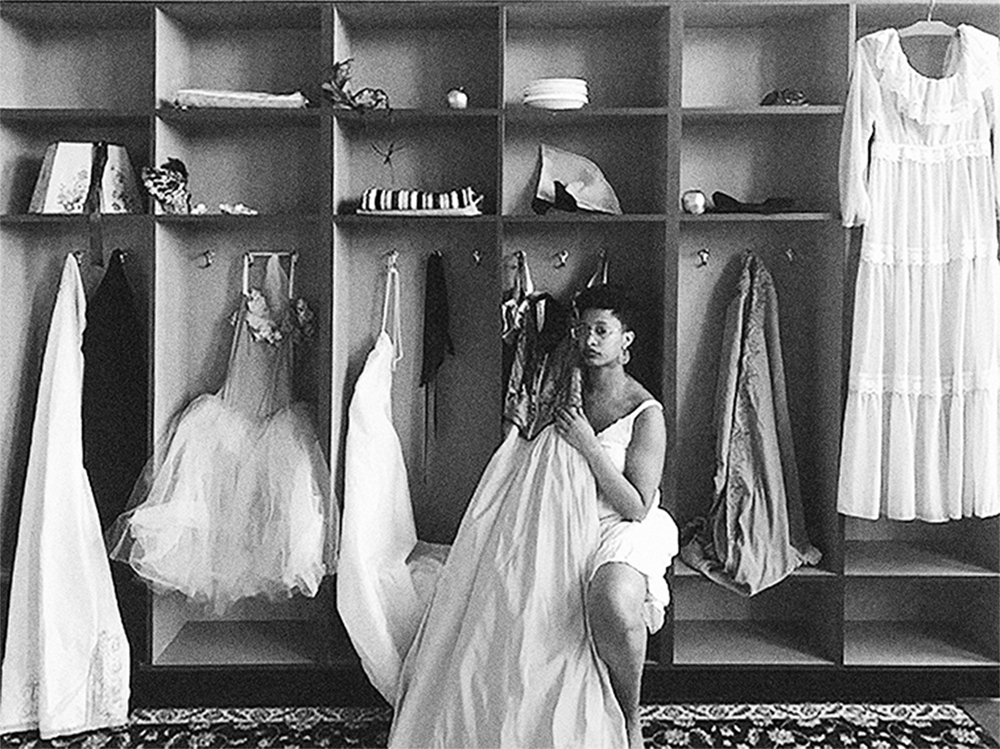

Nafis White describes herself as “an artist, first and foremost.” But, having grown up in a family engaged in advocating for racial justice, being an activist “kind of comes with the territory” as well.

From performance tittled Strand in RISD Museum

White’s work as a “multihyphenate” artist is rooted in different practices and art forms, from dance to sculpture to weaving and hairdressing, which often explore and affirm Black beauty and self-care.

White’s work includes research of Victorian Hair Weaving, in which she reappropriates and reclaims white hair practices from this era for Black hair, working toward colorful, deliberately defiant empowerment -— through “play and continuous exploration.” She emphasizes that in her “appropriation of the Victorian… deep in my heart, I’m just stealing that shit back,” pointing in particular to longstanding Nigerian practices. The different art forms White practices draw on and engage with her own rich ancestry and specific experience of coming from a mixed-race family, as well as the centuries of experience and practice from the broader “Diaspora of experiences and traditions.”

Today, White lives and works in Providence, where she also earned her MFA and BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Today, in addition to practicing her art, she serves as Community Membership Manager for the AS220.

White’s work includes research of Victorian Hair Weaving, in which she reappropriates and reclaims white hair practices from this era for Black hair, working toward colorful, deliberately defiant empowerment -— through “play and continuous exploration.” She emphasizes that in her “appropriation of the Victorian… deep in my heart, I’m just stealing that shit back,” pointing in particular to longstanding Nigerian practices. The different art forms White practices draw on and engage with her own rich ancestry and specific experience of coming from a mixed-race family, as well as the centuries of experience and practice from the broader “Diaspora of experiences and traditions.”

Today, White lives and works in Providence, where she also earned her MFA and BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Today, in addition to practicing her art, she serves as Community Membership Manager for the AS220.