Re-envisoning the Album Cover

as a Statement

Words: Zach Branner

July 15 2021

I don’t remember when I stopped really looking at album covers, titles, or band names.

I know in senior year of high school, Godspeed You! Black Emperor caught my attention with F#A#∞. I loved the exclamation mark, planted like a challenge in the middle of their name, and the anti-commercial spite to put that rarely-printed symbol in the record’s title. It screams out the self-serious anarchy of the band’s music, and quite imperiously demands a few moments to parse. But these days names like ‘Harry Pussy’ and ‘!!!’ slip through my subconscious filing system without incident, needed for documenting the music but not interesting in and of themselves.

![]()

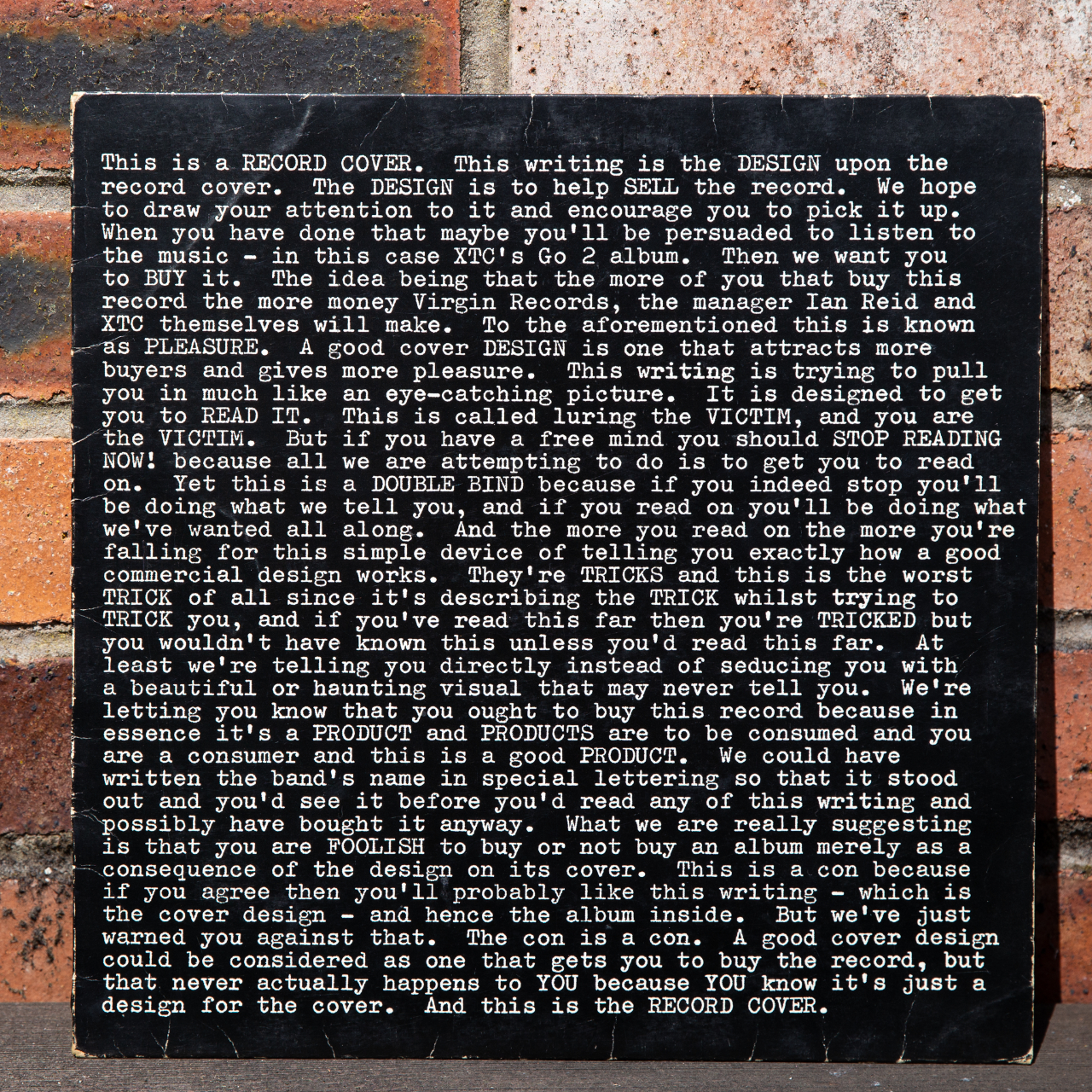

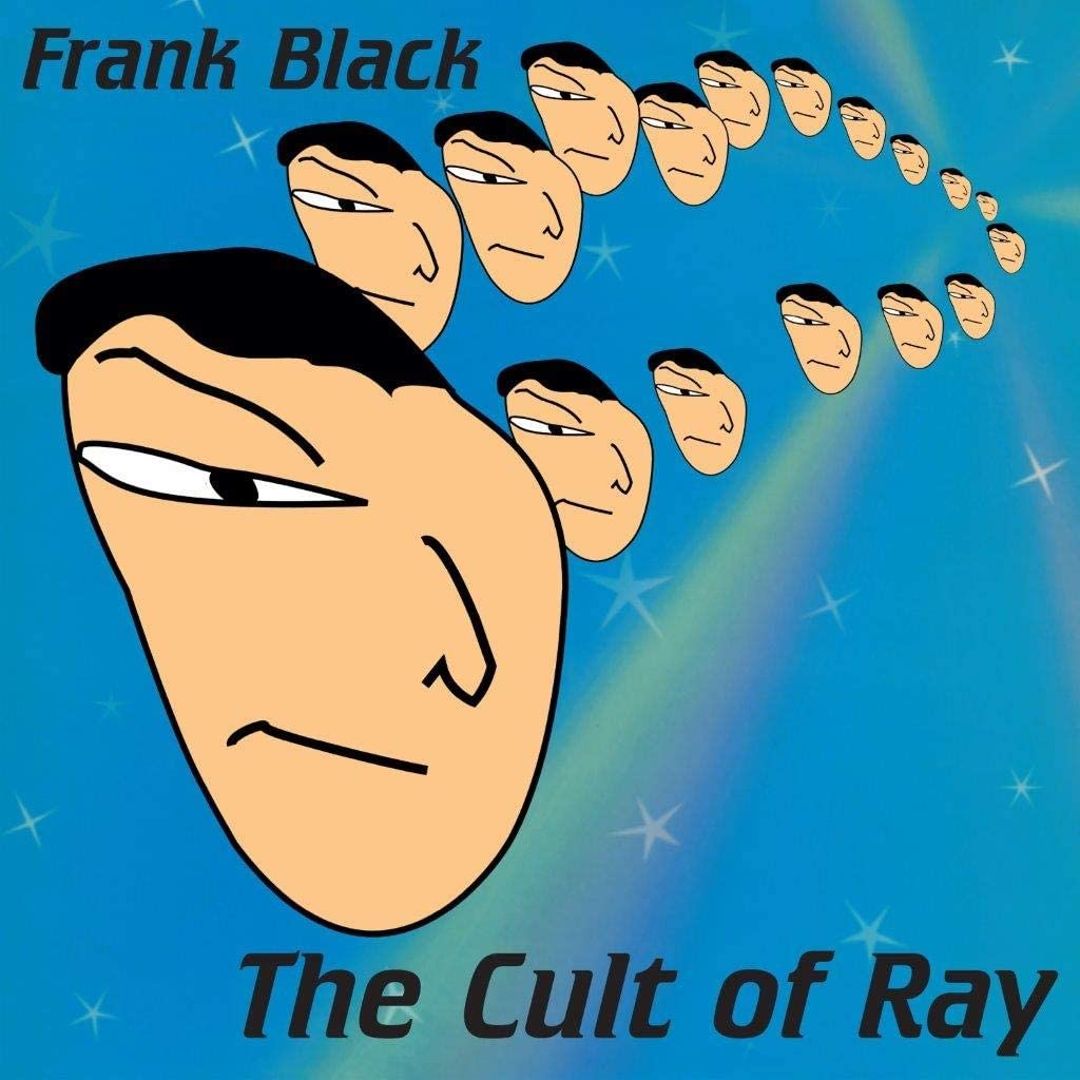

If my cortex detects an album cover that’s a rippled reflection of trees beneath a cloudy sky on the surface of a lake, with the title Urban Driftwood off-center in small italics, I’ll just hear about a new gentle acoustic record, and make a note to listen the next time it rains. When I notice a cover now, it’s either a bad thing (Frank Black’s third solo album The Cult of Ray) or a novelty (XTC’s Go 2).

If my cortex detects an album cover that’s a rippled reflection of trees beneath a cloudy sky on the surface of a lake, with the title Urban Driftwood off-center in small italics, I’ll just hear about a new gentle acoustic record, and make a note to listen the next time it rains. When I notice a cover now, it’s either a bad thing (Frank Black’s third solo album The Cult of Ray) or a novelty (XTC’s Go 2).

This habit developed quickly as a lazy listener who goes through a lot of music, but also because labels (band/album/song names and covers) in music aren’t often discussed directly the way they are in other mediums, like fiction or visual art. I suspect people have been made wary by countless interviews where the band’s asked about a name and the answer is oddly deflating, like it was inspired by a hotel room toilet’s unique gurgle or their old neighbor’s dog. But I also think these tags often become so identified with the music that it never occurs to me to question them separately. That’s a job left to the most devoted fans, the ones who’ve invested a record with so much personal meaning that even the packaging come to seem profound, worthy of the kind of reverent contemplation that monks devote to each holy verse. But the work of these meta-medium tags gets done to me all the same.

![]()

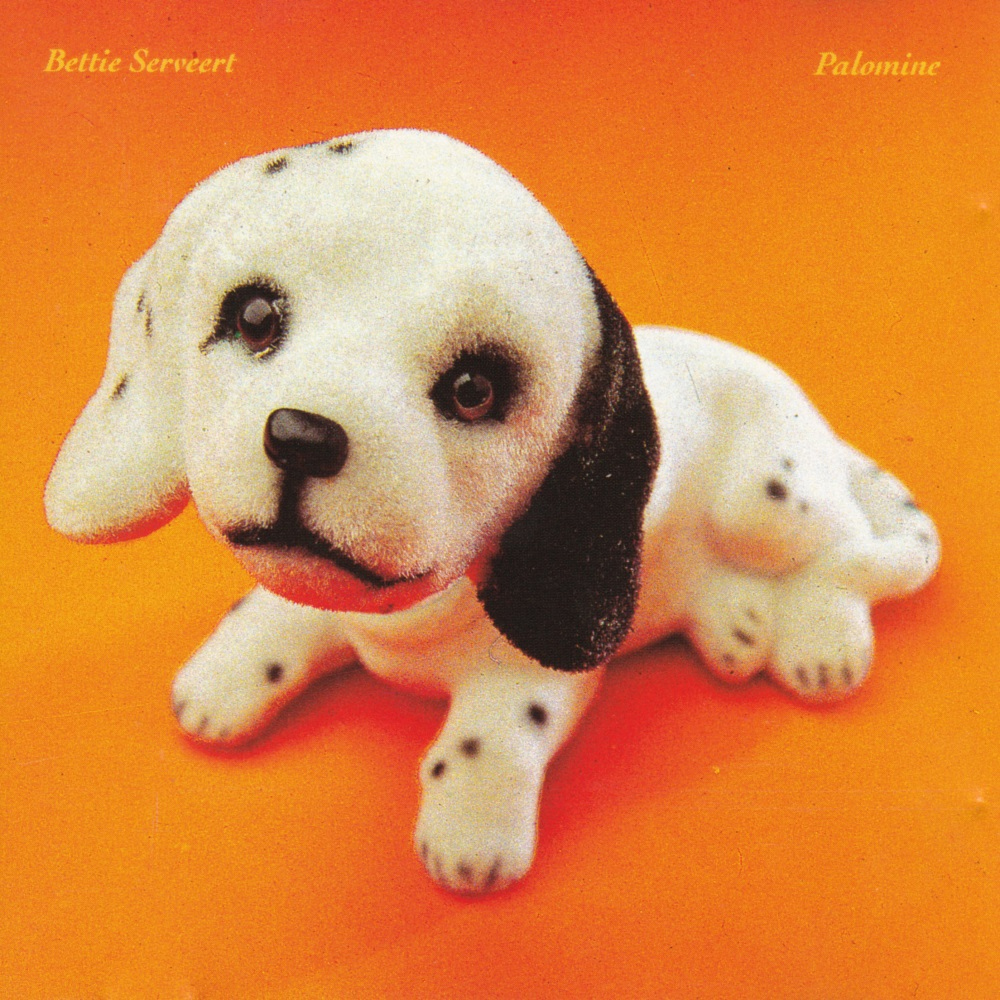

The album cover for Dutch indie act Bettie Serveert’s 1992 debut is off-putting. It’s a puppy, and if the puppy had been cute it’d still be saccharine and juvenile even for guitar pop music aimed at young people. But the puppy is not cute— there’s something wrong about its texture, as though it were out of focus or computer-generated. On a CD case in 1992 this mystery would have quickly solved itself. Only ever seeing shrunken album covers on my phone, though, I got no further than that initial mild distaste. The album’s title confirmed my subconscious sorting mechanism’s impression of toothless pandering—Palomine, a clever or cutesy expression for friend, I guess referring to the dog. The photo was professionally lit and the titles placed maturely across the top, in an inoffensive font, against a bright orange background. It could be a billboard. Put together, in a momentary glance it signalled profit-oriented music made to capitalize on the indie boom. No parent would bar their kid from getting it, but it still caught the eye.

I ran into Palomine in highschool through the radio hit “Tom Boy.” As the type of kid who read Catcher in the Rye unassigned, seeing the cover triggered my hypersensitive phony alert, and I cursed myself for my poser taste. I guiltily downloaded the hit, and never listened to the other tracks. Until this week, when I came across it in my music library and, on a whim, hit play. It turns out “Tom Boy” is the worst song on the record.

Palomine is a great album, I learned this week. Bettie Serveert’s sound is straightforward, but hits the pro chef’s mark of “a lot of little things done well” which lifts it above the genre conventions of early-90s indie rock. For one, the hooks hook. The guitars jangle and echo intimately, spewing feedback for extra muscle where needed, one of them almost always spelling out a compelling phrase to enrich the vocal melody. Guitarists Carol van Dijk and Peter Visser play with a cozy reliability which, together with tempo shifts deftly handled by drummer Berend Dubbe, justify the extra jam time that pushes most tracks past the 2-3 minute mark. Bassist Herman Bunskoeke delivers satisfying lines clearly audible in the mix; his moody (“Brain-Tag”) or delightful (“Tom Boy”) riffs serve similar to Paul McCartney’s bass work on Beatles songs, creating a parallel song that draws you deeper into the track and multiplies its re-listenability. Every piece of the outfit is handled with evident care, which stops the band’s tendency toward gently elegiac pop from becoming trite.

Another powerful weapon in Bettie Serveert’s arsenal is Carol van Dijk’s voice. She and the band are Dutch, but Van Dijk was born in Canada and learned English as her first language. She sings in that unpretentious nasal voice made popular by grunge, but with the strength and range for more powerful melodies. On “Leg” she starts in a precious whisper that unexpectedly flares out in a sneer, and then grows into itself over the course of the song without ever fully showing its cards. She’s a master of this emotional distance; her words resound with conviction, but rarely strike a clear feeling. She warps phrases around the conventional hearing apparently without trying, which evokes an elusive, beleaguered but above-it-all persona, most manifest on “Kid’s Allright”: in deadpan delivery van Dijk sings “And grandma says we’ll turn out bad / Go straight to Hell, just like dad / But don’t get your hopes up high / The kid’s all right.” Other songs tell stories of abandonment, rebellion, isolation, wonder, and resentment, all in first-person narration filled with mysterious details and sharp fragments like “Don’t give the disenfranchised ceilings / It’ll drive them up the wall,” from “This Thing Nowhere”. The only misstep is “Under the Surface,” which cedes too much ground to rock-ballads of earlier decades to weather the rest of the album’s slightly ironic sensibility.

It’s this knowing and ironic attitude that made me re-examine the album art. The theme of feeling outwardly angry and outcast, but really mostly sad, lonely, and confused, a 90s indie staple, seemed at odds with my recollection of the cover’s cheap artifice. I pulled up a larger image on my phone. I imagined myself seeing it for the first time again, knowing now the treasure of its music, searching for any sign of deeper significance.

I saw then what I had missed years ago: the puppy is a stuffed animal.And now, I was able to appreciate the full brilliance of this exalted work. Like a beacon from the divines it revealed its manifold perfection to my humble mind, and I prostrated myself in awe before the infinity of meanings contained within. The illusion of the authentic, the inescapable predations of capital, innocence forever lost and regained only in self-delusion, the insanity and necessity of love, the horror of the real beside the wonder of imagination, and the bald-faced lie of that distinction; it all numbed me into defeated silence. I vowed never to speak again, for everything worth saying had already been said; it would profane the truth to utter these low thoughts, my sullied reflection of that inimitable glory. And so I quit my post and withdrew to the mountains to fulfill my solemn oath, in solitude except for one pal o’ mine.

The album cover for Dutch indie act Bettie Serveert’s 1992 debut is off-putting. It’s a puppy, and if the puppy had been cute it’d still be saccharine and juvenile even for guitar pop music aimed at young people. But the puppy is not cute— there’s something wrong about its texture, as though it were out of focus or computer-generated. On a CD case in 1992 this mystery would have quickly solved itself. Only ever seeing shrunken album covers on my phone, though, I got no further than that initial mild distaste. The album’s title confirmed my subconscious sorting mechanism’s impression of toothless pandering—Palomine, a clever or cutesy expression for friend, I guess referring to the dog. The photo was professionally lit and the titles placed maturely across the top, in an inoffensive font, against a bright orange background. It could be a billboard. Put together, in a momentary glance it signalled profit-oriented music made to capitalize on the indie boom. No parent would bar their kid from getting it, but it still caught the eye.

I ran into Palomine in highschool through the radio hit “Tom Boy.” As the type of kid who read Catcher in the Rye unassigned, seeing the cover triggered my hypersensitive phony alert, and I cursed myself for my poser taste. I guiltily downloaded the hit, and never listened to the other tracks. Until this week, when I came across it in my music library and, on a whim, hit play. It turns out “Tom Boy” is the worst song on the record.

Palomine is a great album, I learned this week. Bettie Serveert’s sound is straightforward, but hits the pro chef’s mark of “a lot of little things done well” which lifts it above the genre conventions of early-90s indie rock. For one, the hooks hook. The guitars jangle and echo intimately, spewing feedback for extra muscle where needed, one of them almost always spelling out a compelling phrase to enrich the vocal melody. Guitarists Carol van Dijk and Peter Visser play with a cozy reliability which, together with tempo shifts deftly handled by drummer Berend Dubbe, justify the extra jam time that pushes most tracks past the 2-3 minute mark. Bassist Herman Bunskoeke delivers satisfying lines clearly audible in the mix; his moody (“Brain-Tag”) or delightful (“Tom Boy”) riffs serve similar to Paul McCartney’s bass work on Beatles songs, creating a parallel song that draws you deeper into the track and multiplies its re-listenability. Every piece of the outfit is handled with evident care, which stops the band’s tendency toward gently elegiac pop from becoming trite.

Another powerful weapon in Bettie Serveert’s arsenal is Carol van Dijk’s voice. She and the band are Dutch, but Van Dijk was born in Canada and learned English as her first language. She sings in that unpretentious nasal voice made popular by grunge, but with the strength and range for more powerful melodies. On “Leg” she starts in a precious whisper that unexpectedly flares out in a sneer, and then grows into itself over the course of the song without ever fully showing its cards. She’s a master of this emotional distance; her words resound with conviction, but rarely strike a clear feeling. She warps phrases around the conventional hearing apparently without trying, which evokes an elusive, beleaguered but above-it-all persona, most manifest on “Kid’s Allright”: in deadpan delivery van Dijk sings “And grandma says we’ll turn out bad / Go straight to Hell, just like dad / But don’t get your hopes up high / The kid’s all right.” Other songs tell stories of abandonment, rebellion, isolation, wonder, and resentment, all in first-person narration filled with mysterious details and sharp fragments like “Don’t give the disenfranchised ceilings / It’ll drive them up the wall,” from “This Thing Nowhere”. The only misstep is “Under the Surface,” which cedes too much ground to rock-ballads of earlier decades to weather the rest of the album’s slightly ironic sensibility.

It’s this knowing and ironic attitude that made me re-examine the album art. The theme of feeling outwardly angry and outcast, but really mostly sad, lonely, and confused, a 90s indie staple, seemed at odds with my recollection of the cover’s cheap artifice. I pulled up a larger image on my phone. I imagined myself seeing it for the first time again, knowing now the treasure of its music, searching for any sign of deeper significance.

I saw then what I had missed years ago: the puppy is a stuffed animal.And now, I was able to appreciate the full brilliance of this exalted work. Like a beacon from the divines it revealed its manifold perfection to my humble mind, and I prostrated myself in awe before the infinity of meanings contained within. The illusion of the authentic, the inescapable predations of capital, innocence forever lost and regained only in self-delusion, the insanity and necessity of love, the horror of the real beside the wonder of imagination, and the bald-faced lie of that distinction; it all numbed me into defeated silence. I vowed never to speak again, for everything worth saying had already been said; it would profane the truth to utter these low thoughts, my sullied reflection of that inimitable glory. And so I quit my post and withdrew to the mountains to fulfill my solemn oath, in solitude except for one pal o’ mine.