Living the Classics:

Elliott Smith’s Elliott Smith (1995)

Words: Alex Purdy

April 18 2022

Elliott Smith Loves You More

With our new series Living the Classics, WBRU is publishing essays on any album from an artist’s back catalog that a writer believes to be classic—whatever the term may mean.

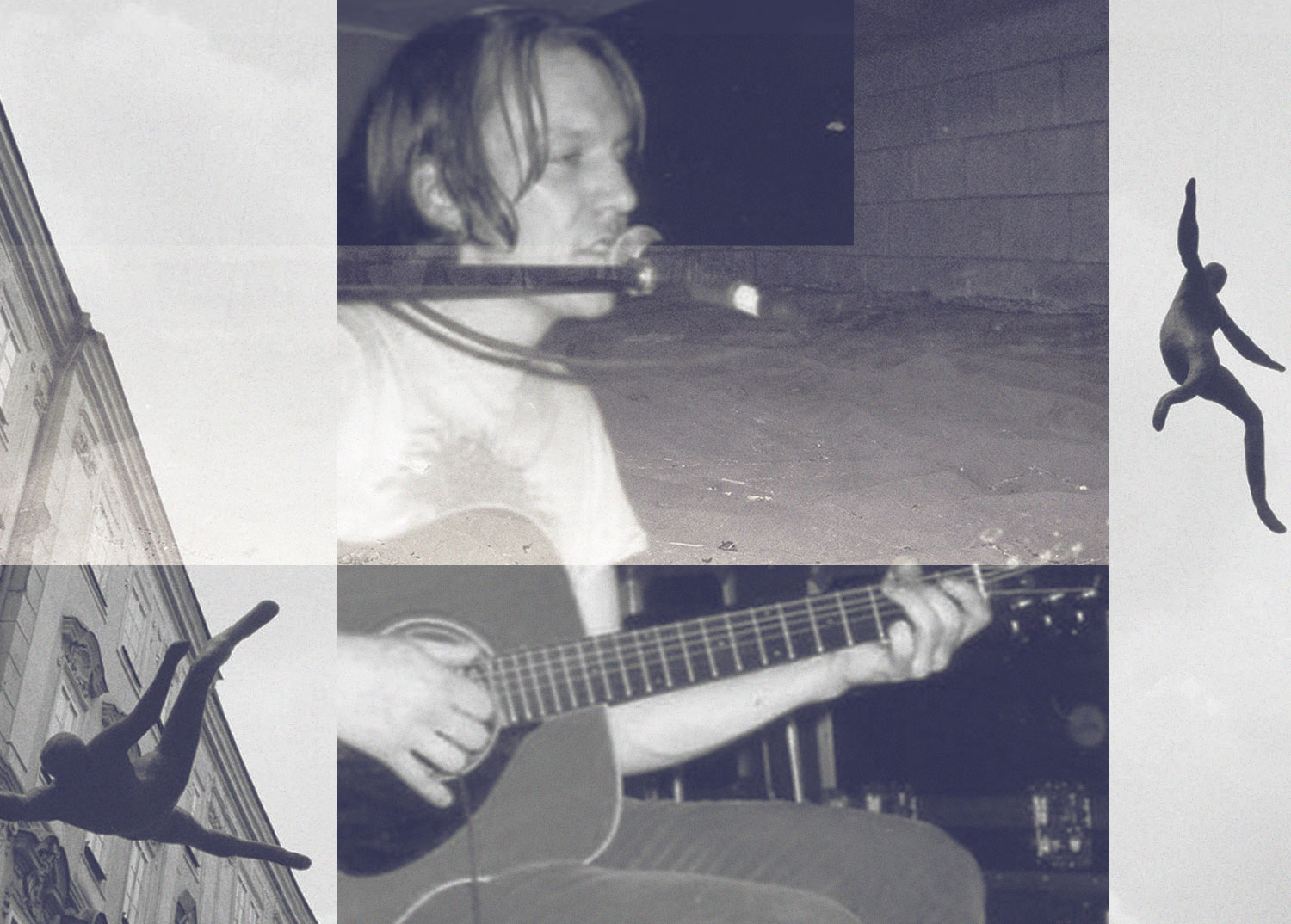

Fall back—before the California rehab stints, MTV interviews, and “Miss Misery” at the Oscars— into someone’s musty Portland basement, where an ex-Texan boy sits with a 8-track Tascam recorder and a well-loved acoustic guitar. Every alternative kid in this small-big city was hardcore (or trying to be) when the early 90s rock scene flushed in—to be the sensitive singer-songwriter covering George Harrison songs was nearly sacrilege. So in the quiet moments between the noisy, punk rock band gigs that burst his smoker’s lungs, Elliott Smith wrote his lovely, vicious songs, his only audience the dog sniffing at the bedroom door.

Elliott Smith’s 1995 self-titled (or untitled, depending on who you ask) album didn’t sell very well. Twelve lo-fi, acoustic tracks driven by delicate fingerpicking, urgent strumming, and vocals a step or two above a whisper, Smith’s sophomore album was radically different from any of the loud, “technically-interesting” rock music his label, Kill Rock Stars, was putting out at the time. It wouldn’t be until after his 1997 album Either/Or that Smith catapulted into national notoriety; yet so many of his fans today name Elliott Smith as their favorite of his works, myself included. Smith said of the album in a March 2000 interview with NME, “at the time I felt it was fully what it was and I had no concern about what people would think of it.” He also recognized that it was by far the darkest of his works at the time. Opening with “Needle in the Hay,” a track which Smith described as a “big ‘fuck you’ song to anybody and everybody,” the album can certainly come off as angsty, and sometimes it is. But Elliott Smith, in all its raw vulnerability and soft grit, has a terrific intimacy, a seductive gravity which entraps you in a violent world you’re not so sure, after all, you want to leave.

Doused in references to heroin track marks, drunken nights of wandering, and getting high on amphetamines, Elliott Smith is, in part, about drug abuse and addiction. But the album goes far beyond a pissy kid’s diary, and in a 1997 interview for Rocket, Smith would later express frustration about all those surface-level interviewers who only “wanted to know why there were so many songs about heroin.” Smith’s drug-infested tales aren’t an end in themselves, but as he explained in the same interview: “I used dope as a vehicle to talk about dependency and non-self-sufficiency. I could have used love as that vehicle, but that’s not where I was.” Smith asks us: What does it mean to cling to the things that destroy you? What if those things—drugs, a codependent relationship, or the melancholy itself—complete you, make you feel loved more than anything else?

Elliott Smith’s 1995 self-titled (or untitled, depending on who you ask) album didn’t sell very well. Twelve lo-fi, acoustic tracks driven by delicate fingerpicking, urgent strumming, and vocals a step or two above a whisper, Smith’s sophomore album was radically different from any of the loud, “technically-interesting” rock music his label, Kill Rock Stars, was putting out at the time. It wouldn’t be until after his 1997 album Either/Or that Smith catapulted into national notoriety; yet so many of his fans today name Elliott Smith as their favorite of his works, myself included. Smith said of the album in a March 2000 interview with NME, “at the time I felt it was fully what it was and I had no concern about what people would think of it.” He also recognized that it was by far the darkest of his works at the time. Opening with “Needle in the Hay,” a track which Smith described as a “big ‘fuck you’ song to anybody and everybody,” the album can certainly come off as angsty, and sometimes it is. But Elliott Smith, in all its raw vulnerability and soft grit, has a terrific intimacy, a seductive gravity which entraps you in a violent world you’re not so sure, after all, you want to leave.

Doused in references to heroin track marks, drunken nights of wandering, and getting high on amphetamines, Elliott Smith is, in part, about drug abuse and addiction. But the album goes far beyond a pissy kid’s diary, and in a 1997 interview for Rocket, Smith would later express frustration about all those surface-level interviewers who only “wanted to know why there were so many songs about heroin.” Smith’s drug-infested tales aren’t an end in themselves, but as he explained in the same interview: “I used dope as a vehicle to talk about dependency and non-self-sufficiency. I could have used love as that vehicle, but that’s not where I was.” Smith asks us: What does it mean to cling to the things that destroy you? What if those things—drugs, a codependent relationship, or the melancholy itself—complete you, make you feel loved more than anything else?

I can’t be myself

I can’t be myself and I don’t want to talk.

I’m taking the cure so I can be quiet wherever I want.

– “Needle in the Hay”

I can’t be myself and I don’t want to talk.

I’m taking the cure so I can be quiet wherever I want.

– “Needle in the Hay”

I wouldn’t need a hero

if I wasn’t such a zero.

– “Good to Go”

if I wasn’t such a zero.

– “Good to Go”

Press play on “Coming up Roses” and fall into the orbit of a stunted desire. It’s the most upbeat song on the album, carrying the listener through to a blissed-out optimism when Smith sings in the chorus, “...and you’re coming up roses, everywhere you go, red roses follow.” “Coming up roses” is an old saying which means that everything’s turning out fine—but the narrator’s euphoria is abrupt and unstable, balanced precariously on Smith’s wavering voice. Just as soon as we blossom up into hopefulness, we slip back down along the slants of stepped-down tuning and Smith’s relentless double-tracked whispers: so you got in a kind of trouble that nobody knows. As Genius annotator NKMNCambo notes, “coming up roses” is also a common slang term for some intravenous drug (most often heroin) users, referring to the flash of blood in the syringe just before the plunger goes down and the user gets high. It’s heroin which can get this user up to a world where everything’s alright, but it’s not too long until, once again, they’re “buried below.”

The deep, inevitable gravity which pervades across this song (and all of Elliott Smith) operates not only to illustrate the highs and lows of drug abuse, but also to show us the ways seduction characterizes addiction— that dependency can be a fucked-up kind of love. On “The White Lady Loves You More,” Smith brings us into the world of a tragic couple whose love for one another can’t overcome the siren’s call of addiction. The narrator, knowing that they could never give to their addicted lover what heroin can, sings, “the white lady loves you more.” You just want her to do anything to you, there ain’t nothing that you won’t allow. For this addict, it’s not a failure to care for their partner, but rather a collapse into a surer love— the promise of the come-up, the certainty of the fall.

![]()

Smith’s cast of dependents are passive figures, not only in the sense that they all rely on alcohol, heroin, or anything else to get through the day, but they’re so often stagnant, laying still among the remnants of some life passed by. In “Good to Go,” the narrator laments: “All I ever see ‘round here is things of hers that you left lying around.” In this graveyard of lost connections, our narrator closes out the song with this: “I’m waiting for something that’s not coming.” There’s a lot of waiting around in Smith’s music. It’s a simple, striking image of passive anticipation, a desire to get yourself unstuck without having the strength to move, of an already-foreclosed hope. The closing track, “The Biggest Lie,” opens with the line: “I’m waiting for the train, the subway that only goes one way.” Whether he’s made up his mind to jump, or he’s about to set off for good, Smith only shows us the moments before the action—he suspends us above the anticipation of what could be an end, a beginning, or a choice.

In angrier songs, the characters of Elliott Smith affirm: Don’t be cross, this sick I want. But most often, they wait. Sometimes they wait for something better, sometimes they just wait for it all to end—but there’s always a chance for something to change in those last remaining moments. To Rolling Stone in 1998, Smith explained the three kinds of tracks he makes: his “fuck you” songs, the songs that “try to chronicle other people’s lives,” and the last, “the ‘I’m going to insist that things can work out, and I’ll never stop insisting that they can work out’” songs. While it’s much easier to see things working out in Smith’s later, sweeter albums, there’s something about waiting—even for the train that’s going to kill you—that in itself feels hopeful, absolutely alive. In one way, Smith’s characters are empty skins, dependents in endless orbit about their addictions. But in another, isn’t there some time left, even a second or two, for things to work out?

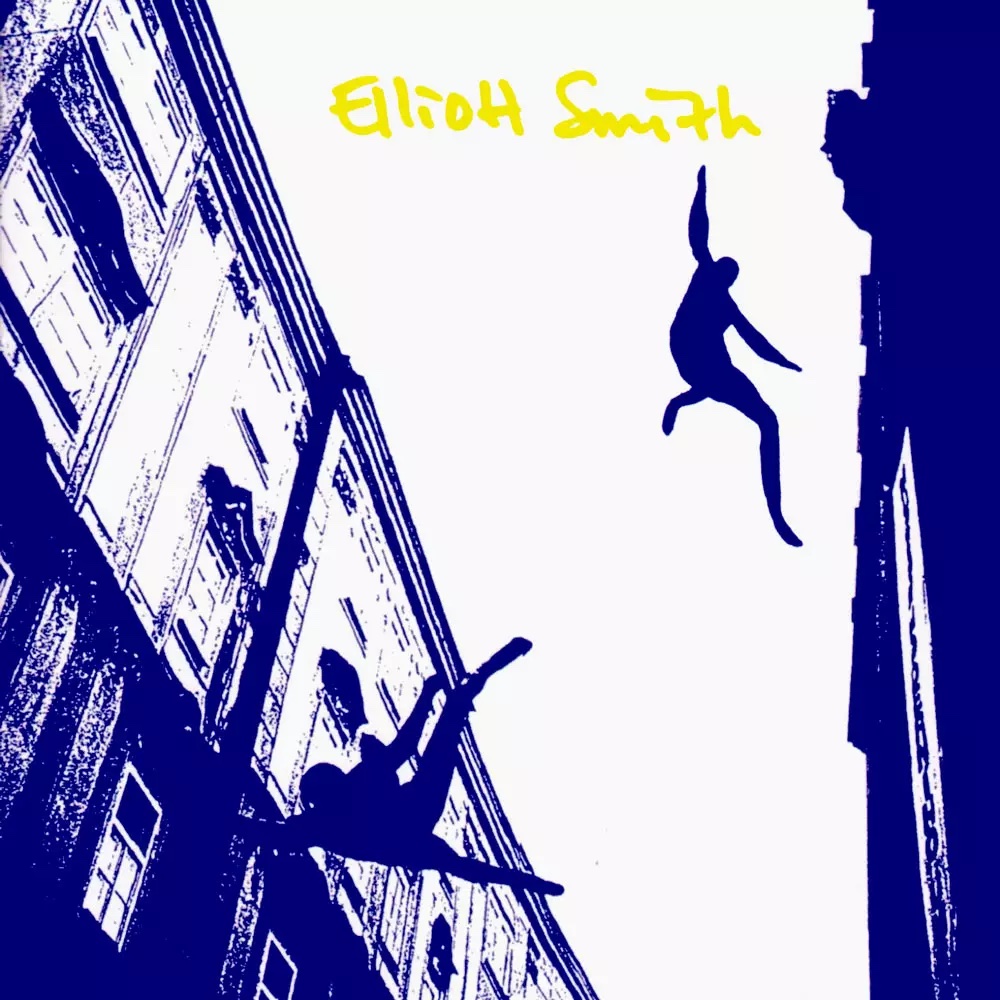

Look towards the front cover. Two figures are suspended in the air, one above the other. They’re falling—we don’t know if they jumped or tripped, whether they want this or not. We’re already anticipating the end, the final crash to the ground, the inevitable smack. But the figures don’t move, and we, like them, are left stagnant, endlessly waiting. It could be a cruel trick, gravity suspending its will to entrap us in this airy oblivion. But it could also be a chance, an invitation to reclaim agency, to try to live. There’s time. You could wrench yourself around this last moment, escape the orbit, and fly.

Elliott Smith has a gravity of its own. Like a demo from a friend, it’s got lo-fi squeaks and delicate vocals with all the intimacy of human imperfection. Smith asks you to lean in close as he whispers confessions, the raw kinds of things you might tell a loved one far after midnight. Even as he leaves you slumped on the side of some road you hope you won’t recognize, Smith gives you the kind of closeness that can be hard to come by, and even harder to leave. He gave it to me. I lived in this album for a long time, waiting for something. But there’s time, I see it now. I’m finding my way out of orbit.

The deep, inevitable gravity which pervades across this song (and all of Elliott Smith) operates not only to illustrate the highs and lows of drug abuse, but also to show us the ways seduction characterizes addiction— that dependency can be a fucked-up kind of love. On “The White Lady Loves You More,” Smith brings us into the world of a tragic couple whose love for one another can’t overcome the siren’s call of addiction. The narrator, knowing that they could never give to their addicted lover what heroin can, sings, “the white lady loves you more.” You just want her to do anything to you, there ain’t nothing that you won’t allow. For this addict, it’s not a failure to care for their partner, but rather a collapse into a surer love— the promise of the come-up, the certainty of the fall.

Smith’s cast of dependents are passive figures, not only in the sense that they all rely on alcohol, heroin, or anything else to get through the day, but they’re so often stagnant, laying still among the remnants of some life passed by. In “Good to Go,” the narrator laments: “All I ever see ‘round here is things of hers that you left lying around.” In this graveyard of lost connections, our narrator closes out the song with this: “I’m waiting for something that’s not coming.” There’s a lot of waiting around in Smith’s music. It’s a simple, striking image of passive anticipation, a desire to get yourself unstuck without having the strength to move, of an already-foreclosed hope. The closing track, “The Biggest Lie,” opens with the line: “I’m waiting for the train, the subway that only goes one way.” Whether he’s made up his mind to jump, or he’s about to set off for good, Smith only shows us the moments before the action—he suspends us above the anticipation of what could be an end, a beginning, or a choice.

In angrier songs, the characters of Elliott Smith affirm: Don’t be cross, this sick I want. But most often, they wait. Sometimes they wait for something better, sometimes they just wait for it all to end—but there’s always a chance for something to change in those last remaining moments. To Rolling Stone in 1998, Smith explained the three kinds of tracks he makes: his “fuck you” songs, the songs that “try to chronicle other people’s lives,” and the last, “the ‘I’m going to insist that things can work out, and I’ll never stop insisting that they can work out’” songs. While it’s much easier to see things working out in Smith’s later, sweeter albums, there’s something about waiting—even for the train that’s going to kill you—that in itself feels hopeful, absolutely alive. In one way, Smith’s characters are empty skins, dependents in endless orbit about their addictions. But in another, isn’t there some time left, even a second or two, for things to work out?

Look towards the front cover. Two figures are suspended in the air, one above the other. They’re falling—we don’t know if they jumped or tripped, whether they want this or not. We’re already anticipating the end, the final crash to the ground, the inevitable smack. But the figures don’t move, and we, like them, are left stagnant, endlessly waiting. It could be a cruel trick, gravity suspending its will to entrap us in this airy oblivion. But it could also be a chance, an invitation to reclaim agency, to try to live. There’s time. You could wrench yourself around this last moment, escape the orbit, and fly.

Elliott Smith has a gravity of its own. Like a demo from a friend, it’s got lo-fi squeaks and delicate vocals with all the intimacy of human imperfection. Smith asks you to lean in close as he whispers confessions, the raw kinds of things you might tell a loved one far after midnight. Even as he leaves you slumped on the side of some road you hope you won’t recognize, Smith gives you the kind of closeness that can be hard to come by, and even harder to leave. He gave it to me. I lived in this album for a long time, waiting for something. But there’s time, I see it now. I’m finding my way out of orbit.