Living the Classics:

Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill (1986)

Words: Angelina Rios-Galindo

April 28 2022

You’ve just met the person at the function who stands on one side of the room and recites the lyrics of whatever song comes on, aggressively looking around for a gaze of validation. They proudly claim they’ve been told they have the “gift of the gab,” but you quickly realize that they’re actually just insufferable and talk too much—it’s not so much pride as it is hubris.

With our new series Living the Classics, WBRU is publishing essays on any album from an artist’s back catalog that a writer believes to be classic—whatever the term may mean.

You change the subject and ask them about their stack of CDs (they tell you that you’ve probably never heard of anything before), and are pleasantly surprised to hear the rumbling beginnings of “Rhymin & Stealin,” the opening song on an album that rings like it should be played out of blown speakers that have been used as coasters one too many times. You’re hooked. Obviously.

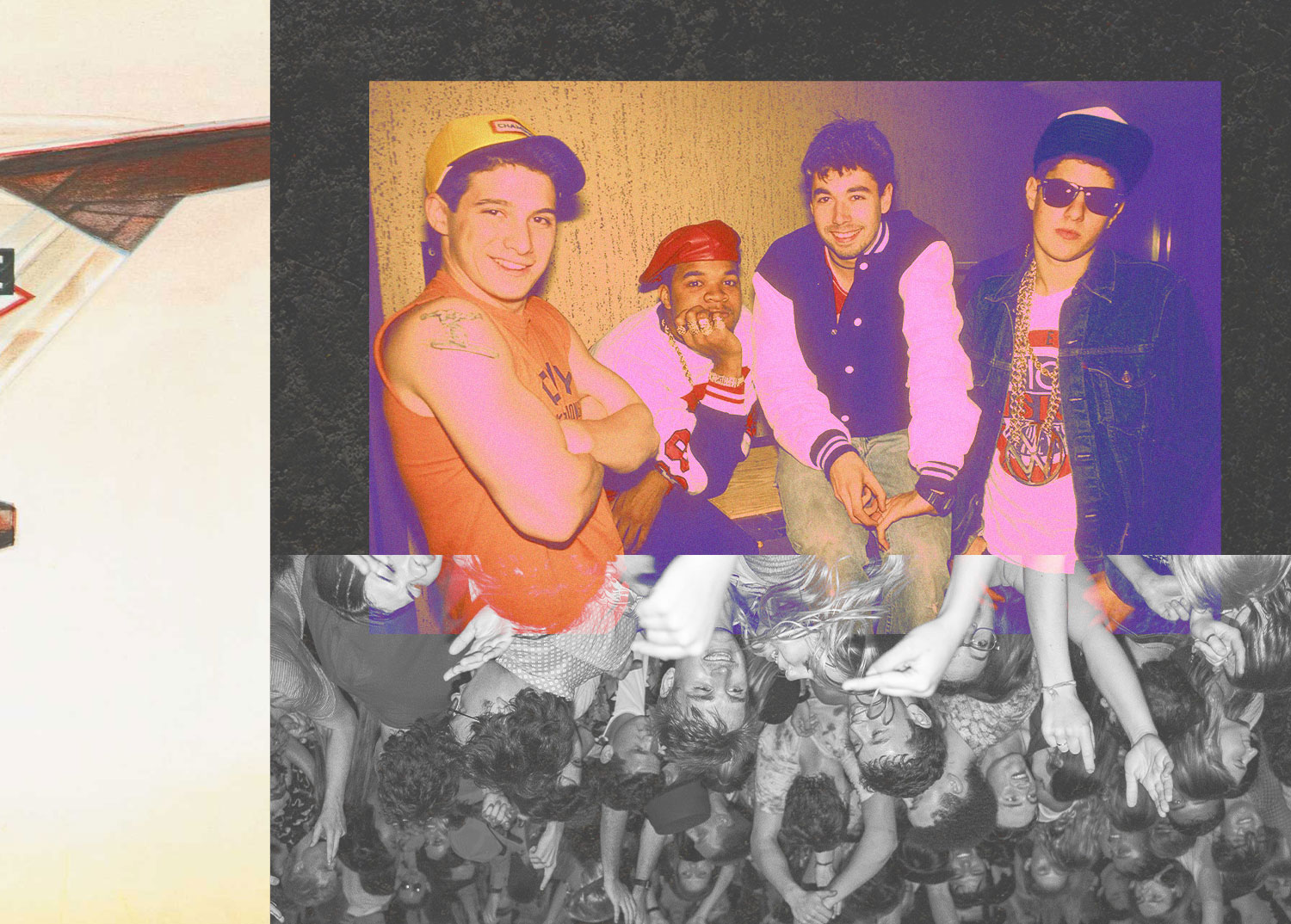

Licensed to Ill, released in 1986—and premiering Beastie Boys in their engagement with Rick Rubin and his Def Jam Recordings—lit the rap sphere on fire. The production was gritty and the edges unpolished, much like the inner workings of the baby label itself, which had, 2 years earlier, spawned from the peeled linoleum and (I’m assuming) blue plaid bedspread of Rubin’s NYU dorm. The Boys’ new, resounding presence—somewhat undercut in concept by the release of King of Rock by Run-D.M.C. the year before—was calculated: a crunchy, slightly hard-to-digest combination of hip-hop, rap, punk, rock, metal, and (of course) friendship. Beastie Boys, in this way, began to bridge the traditionally disparate sounds of upper middle-class whitehood and the largely working-class noise of Black and brown artists, funneled through the lens of three early 20-somethings from New York.

The perspective of this album was genius and backwards, a parodied representation of the die-hard frat boy lifestyle that mimicked the boys’ own recklessness, yet was antithetical to their real beliefs. Perhaps not obviously enough, Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz, Adam “MCA” Yauch, and Michael “Mike D” Diamond wrestled with collegiate misogyny, alcoholism, homophobia, and quintessential fraternal buffoonery with abrasive, provocative lyrics that you just can’t stop listening to.

Sixth on the album, “Girls” is probably the most obviously satirical track on Licensed to Ill. The blatant sexism of the lyrics reads so clearly laid overtop the “Ring for Service” bell-like underscore that at first is appalling, then in a feat of Stockholm syndrome, becomes almost laudable.

Licensed to Ill, released in 1986—and premiering Beastie Boys in their engagement with Rick Rubin and his Def Jam Recordings—lit the rap sphere on fire. The production was gritty and the edges unpolished, much like the inner workings of the baby label itself, which had, 2 years earlier, spawned from the peeled linoleum and (I’m assuming) blue plaid bedspread of Rubin’s NYU dorm. The Boys’ new, resounding presence—somewhat undercut in concept by the release of King of Rock by Run-D.M.C. the year before—was calculated: a crunchy, slightly hard-to-digest combination of hip-hop, rap, punk, rock, metal, and (of course) friendship. Beastie Boys, in this way, began to bridge the traditionally disparate sounds of upper middle-class whitehood and the largely working-class noise of Black and brown artists, funneled through the lens of three early 20-somethings from New York.

The perspective of this album was genius and backwards, a parodied representation of the die-hard frat boy lifestyle that mimicked the boys’ own recklessness, yet was antithetical to their real beliefs. Perhaps not obviously enough, Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz, Adam “MCA” Yauch, and Michael “Mike D” Diamond wrestled with collegiate misogyny, alcoholism, homophobia, and quintessential fraternal buffoonery with abrasive, provocative lyrics that you just can’t stop listening to.

Sixth on the album, “Girls” is probably the most obviously satirical track on Licensed to Ill. The blatant sexism of the lyrics reads so clearly laid overtop the “Ring for Service” bell-like underscore that at first is appalling, then in a feat of Stockholm syndrome, becomes almost laudable.

Girls, to do the dishes

Girls, to clean up my room

Girls, to do the laundry

Girls, and in the bathroom

Girls, that’s all I really want is girls

— “Girls”

Here, as in most of the Beastie Boys discography, Ad-Rock's shrill, buoyant whine is unmistakable. He boasts about his role as the man in charge—the titular Girls under the thumb of his jurisdiction—so convincingly that it’s almost impossible to believe he’s not actually a misogynist. His life beyond the band, though, indicates a remarkable cognizance of and sensitivity to sexism littering his field. In the years following the release of Licensed to Ill, Adam Horovitz would prove, time and again, to be an unlikely advocate for female liberation and the protection of women in the music industry.

In 1999, Beastie Boys accepted the Best Hip Hop Music Video VMA at the MTV Music Awards for “Intergalactic,” the first single off their fifth album Hello Nasty. Horovitz took to that stage and called unto other artists to hold themselves and their fans accountable in the wake of that year’s disastrous Woodstock. Retroactively discerned “the day the Nineties died,” Woodstock ‘99 stirred a cataclysm of heat- and sanitation-related deaths, reports of sexual assault, and instances of violence that reframed the narrative of music festivals at large. Many artists, including Mary J Blige and Metallica’s Lars Ulrich, applauded him for speaking out, while other headliners like Fred Durst of Limp Bizkit made no acknowledgement of the issue whatsoever. In 2006, twenty years after Licensed to Ill was released, Horovitz married Kathleen Hanna, who pioneered the Riot Grrrl movement by leading the landmark ‘90s feminist-punk bands Bikini Kill and Le Tigre. Championing the feminine infiltration of the male-dominated punk scene (along with Hole’s Courtney Love and Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth), Hanna revolutionized the plane of women’s rights at its intersection with music, as Ad-Rock supported her along the way.

“Slow Ride,” the track just before “Girls,” glamorizes the lifestyle of sitting at home and doing absolutely nothing yet still coming out on top. The production itself is lazy and unbecoming, drawing a sped-up sample from War’s “Low Rider,” the title of the Boys’ track remaining so similar that it becomes a question of homage or lackadaisy. The lyrics conjure an image of the winningest antihero you love to hate—someone who really could not care less about the world around them, moving as if their haters loom by the thousands.

Adam Yauch, among other things, was a fervent advocate for religious freedom. Starting in 1996, MCA organized benefit concerts to aid the Tibetan freedom movement, looping in artists like the Smashing Pumpkins, Rage Against the Machine, and REM. Continuing into 1999 and across four continents, Beastie Boys fundraised millions of dollars for Tibetan monks and refugees after Yauch himself converted to Buddhism in 1994. In 1998, at the MTV Music Awards, he condemned the abhorrent treatment that citizens of Islamic faith in the US faced (and continue to face) and publicly contested American aggression in the Middle East.

In May 2013, on the first anniversary of Yauch’s tragic passing, the Palmetto Playground in Brooklyn was renamed in his honor—later vandalized with antisemitic symbols and phrases in 2016, targeting Yauch’s Jewish heritage. As a result, Ad-Rock has been vocal in recent years about the inequities and hardships that Jewish Americans are subjected to on a daily basis, taking heed in addition to his lived experiences with Hanna and the feminist punk scene.

Diamond’s activism is certainly rooted in the home and the empowerment of individuals to make tangible change, with emphasis on the environment and family dynamics. In response to critiques of sexism on Licensed to Ill, Mike D was outspoken about supporting victims of domestic violence, especially as written into Beastie Boys’ subsequent projects like second studio album Paul’s Boutique. In the early 2000s, he began sharing with the media his working passion for environmentalism and conservation, partnering with Reverb to bring recycling sites to Beastie Boys shows and encouraging fans to bring their empty bottles, cans, and e-waste.

In hindsight, being partially what makes Licensed to Ill one of the classics, it’s pretty obvious that Beastie Boys’ first project is burlesque. While maybe initially off-putting, the flow of the lyrics poured over the tone of the John Bonham-inspired drums is addictive. “Fight for Your Right,” statistically the most popular song on the album, is the perfect party anthem—albeit celebrated in vain by the sophomoric audience they were making fun of in the first place—begging the conversation of an artist’s responsibility to tend the interpretation of their art.

Ultimately, much of their response was that, of course, they didn’t literally mean many of the things they said in the album, but that that was the beauty of it. It was their first official project, not meant to be taken seriously or scrutinously examined, but meant to make fun of people and to be made fun of. Licensed to Ill was exactly what America needed on the brink of the ‘90s—an egotistical, genre-melting, incoherent celebration of life framed in poor taste by three white boys who did, in fact, change the scope of music, but who also didn’t really care.

In 1999, Beastie Boys accepted the Best Hip Hop Music Video VMA at the MTV Music Awards for “Intergalactic,” the first single off their fifth album Hello Nasty. Horovitz took to that stage and called unto other artists to hold themselves and their fans accountable in the wake of that year’s disastrous Woodstock. Retroactively discerned “the day the Nineties died,” Woodstock ‘99 stirred a cataclysm of heat- and sanitation-related deaths, reports of sexual assault, and instances of violence that reframed the narrative of music festivals at large. Many artists, including Mary J Blige and Metallica’s Lars Ulrich, applauded him for speaking out, while other headliners like Fred Durst of Limp Bizkit made no acknowledgement of the issue whatsoever. In 2006, twenty years after Licensed to Ill was released, Horovitz married Kathleen Hanna, who pioneered the Riot Grrrl movement by leading the landmark ‘90s feminist-punk bands Bikini Kill and Le Tigre. Championing the feminine infiltration of the male-dominated punk scene (along with Hole’s Courtney Love and Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth), Hanna revolutionized the plane of women’s rights at its intersection with music, as Ad-Rock supported her along the way.

“Slow Ride,” the track just before “Girls,” glamorizes the lifestyle of sitting at home and doing absolutely nothing yet still coming out on top. The production itself is lazy and unbecoming, drawing a sped-up sample from War’s “Low Rider,” the title of the Boys’ track remaining so similar that it becomes a question of homage or lackadaisy. The lyrics conjure an image of the winningest antihero you love to hate—someone who really could not care less about the world around them, moving as if their haters loom by the thousands.

Because I’m hard hittin’, always bitten, cool as hell

I got trees on my mirror so my car won’t smell

Sittin’ around the house, gettin’ high and watchin’ tube

Eatin’ Colonel’s chicken, drinkin’ Heineken brew,

I’m a gangster, I’m a prankster, I’m the king of the Ave.

I’m hated, confronted for the juice that I have

All the fly ladies are making a fuss

But I can’t pay attention, cause I’m on that dust

— “Slow Ride”

The sentiment of this song certainly grew indicative of the “IDGAF, I do what I want” attitude of the archetypal Frat Boy that Beastie Boys were hoping to channel, reflecting on and critiquing their identities as immature young men, while nonetheless operating in opposition to the reality of the their values. Expressed most clearly through their efforts post-Licensed to Ill, Ad-Rock, MCA, and Mike D served and continue to serve as avid proponents of social movements, both progressive and restorative.I got trees on my mirror so my car won’t smell

Sittin’ around the house, gettin’ high and watchin’ tube

Eatin’ Colonel’s chicken, drinkin’ Heineken brew,

I’m a gangster, I’m a prankster, I’m the king of the Ave.

I’m hated, confronted for the juice that I have

All the fly ladies are making a fuss

But I can’t pay attention, cause I’m on that dust

— “Slow Ride”

Adam Yauch, among other things, was a fervent advocate for religious freedom. Starting in 1996, MCA organized benefit concerts to aid the Tibetan freedom movement, looping in artists like the Smashing Pumpkins, Rage Against the Machine, and REM. Continuing into 1999 and across four continents, Beastie Boys fundraised millions of dollars for Tibetan monks and refugees after Yauch himself converted to Buddhism in 1994. In 1998, at the MTV Music Awards, he condemned the abhorrent treatment that citizens of Islamic faith in the US faced (and continue to face) and publicly contested American aggression in the Middle East.

In May 2013, on the first anniversary of Yauch’s tragic passing, the Palmetto Playground in Brooklyn was renamed in his honor—later vandalized with antisemitic symbols and phrases in 2016, targeting Yauch’s Jewish heritage. As a result, Ad-Rock has been vocal in recent years about the inequities and hardships that Jewish Americans are subjected to on a daily basis, taking heed in addition to his lived experiences with Hanna and the feminist punk scene.

Diamond’s activism is certainly rooted in the home and the empowerment of individuals to make tangible change, with emphasis on the environment and family dynamics. In response to critiques of sexism on Licensed to Ill, Mike D was outspoken about supporting victims of domestic violence, especially as written into Beastie Boys’ subsequent projects like second studio album Paul’s Boutique. In the early 2000s, he began sharing with the media his working passion for environmentalism and conservation, partnering with Reverb to bring recycling sites to Beastie Boys shows and encouraging fans to bring their empty bottles, cans, and e-waste.

In hindsight, being partially what makes Licensed to Ill one of the classics, it’s pretty obvious that Beastie Boys’ first project is burlesque. While maybe initially off-putting, the flow of the lyrics poured over the tone of the John Bonham-inspired drums is addictive. “Fight for Your Right,” statistically the most popular song on the album, is the perfect party anthem—albeit celebrated in vain by the sophomoric audience they were making fun of in the first place—begging the conversation of an artist’s responsibility to tend the interpretation of their art.

Your pops caught you smoking, and he says “No way!”

That hypocrite smokes two packs a day

Man, living at home is such a drag

Now your mom threw away your best porno mag (bust it!)

You gotta fight for your right to party!

— “Fight for Your Right”

If an artist’s work centers social commentary in a way that isn’t inherently explicit, do they—can they—contribute to the very thing that they are criticizing? For Beastie Boys, if the irony of Licensed to Ill is unironically adopted into frat culture itself, are the sentiments of anti-misogyny, anti-homophobia, and otherwise falsely translated? Or, is it possible that listeners don’t absorb their words, but are instead simply attracted to the myriad influences of Misfits, Bad Brains, Kool & The Gang, and Deep Purple? In years after the album’s release, all three Beastie Boys frequently battled such questions in interviews and from (sometimes hesitant) fans.That hypocrite smokes two packs a day

Man, living at home is such a drag

Now your mom threw away your best porno mag (bust it!)

You gotta fight for your right to party!

— “Fight for Your Right”

Ultimately, much of their response was that, of course, they didn’t literally mean many of the things they said in the album, but that that was the beauty of it. It was their first official project, not meant to be taken seriously or scrutinously examined, but meant to make fun of people and to be made fun of. Licensed to Ill was exactly what America needed on the brink of the ‘90s—an egotistical, genre-melting, incoherent celebration of life framed in poor taste by three white boys who did, in fact, change the scope of music, but who also didn’t really care.

Meticulous, experimental, and also sort of an accident, the signature snare and reverb of Beastie Boys’ “Paul Revere” so perfectly reflects the conglomerate existence of Licensed to Ill and its massive impact on the hip-hop community. It paints a fictional picture of the way the Boys met, their individual antics colliding as outlaws set sometime in the realm of the Wild West.

At 3 minutes and 40 seconds long, “Paul Revere” has so many layers, each one peeled back with guilty pleaseure. Every line is robust and surprising, no time to contemplate one before being taken aback by the next. Each Beastie Boy takes on their own character, toting guns and wreaking havoc while on the run, yet still making out at the end with their loot—much like their reign in the era of Licensed to Ill.

At 3 minutes and 40 seconds long, “Paul Revere” has so many layers, each one peeled back with guilty pleaseure. Every line is robust and surprising, no time to contemplate one before being taken aback by the next. Each Beastie Boy takes on their own character, toting guns and wreaking havoc while on the run, yet still making out at the end with their loot—much like their reign in the era of Licensed to Ill.

Now here's a little story I got to tell

About three bad brothers you know so well

It started way back in history

With Ad-Rock, MCA and me, Mike D

...

Mike D grabbed the money, MCA snatched the gold

I grabbed two girlies and a beer that’s cold

– “Paul Revere”

Not barring controversy, Beastie Boys’ debut album broke records and received an unprecedented range of accolades. Rolling Stone magazine, throughout years of reranking, consistently includes Licensed to Ill in their list of the “500 greatest albums of all time,” claiming in 2013 that it remains “the best debut album of all time.” Q magazine, a popular music publication based in the UK before its final issue in summer 2020, cited the album as the only project to properly bridge rap with punk rock, even arguing its precedence over Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks. The Source, America’s longest-running and most prevalent rap periodical, praised Licensed to Ill—in 2002 becoming the first Jewish hip-hop album to receive the lucrative 5 Mic distinction. In March of 1987, the Boys made history, championing the first rap album to hit number one on the Billboard 200.

It would be trite and presumptuous to say that Licensed to Ill changed music forever, but that’s exactly what Beastie Boys embodied. As calculated as they were spontaneous, there has yet to be a rap/punk/rock group able to both upset and excite so many people at once, since the smashing debut of this self-revering, slightly intolerable trio from Brooklyn and the 13 tracks on their first album.

It would be trite and presumptuous to say that Licensed to Ill changed music forever, but that’s exactly what Beastie Boys embodied. As calculated as they were spontaneous, there has yet to be a rap/punk/rock group able to both upset and excite so many people at once, since the smashing debut of this self-revering, slightly intolerable trio from Brooklyn and the 13 tracks on their first album.