From J. Balvin to Justin Bieber:

The Emergence of Spanish Language Music in Mainstream Pop

Words: WBRU

August 18, 2019

Spanish language music is increasing in popularity, characterized by its fun, danceable sounds. WBRU looks into the sudden globalization of the style and what happens when culture turns to trend.

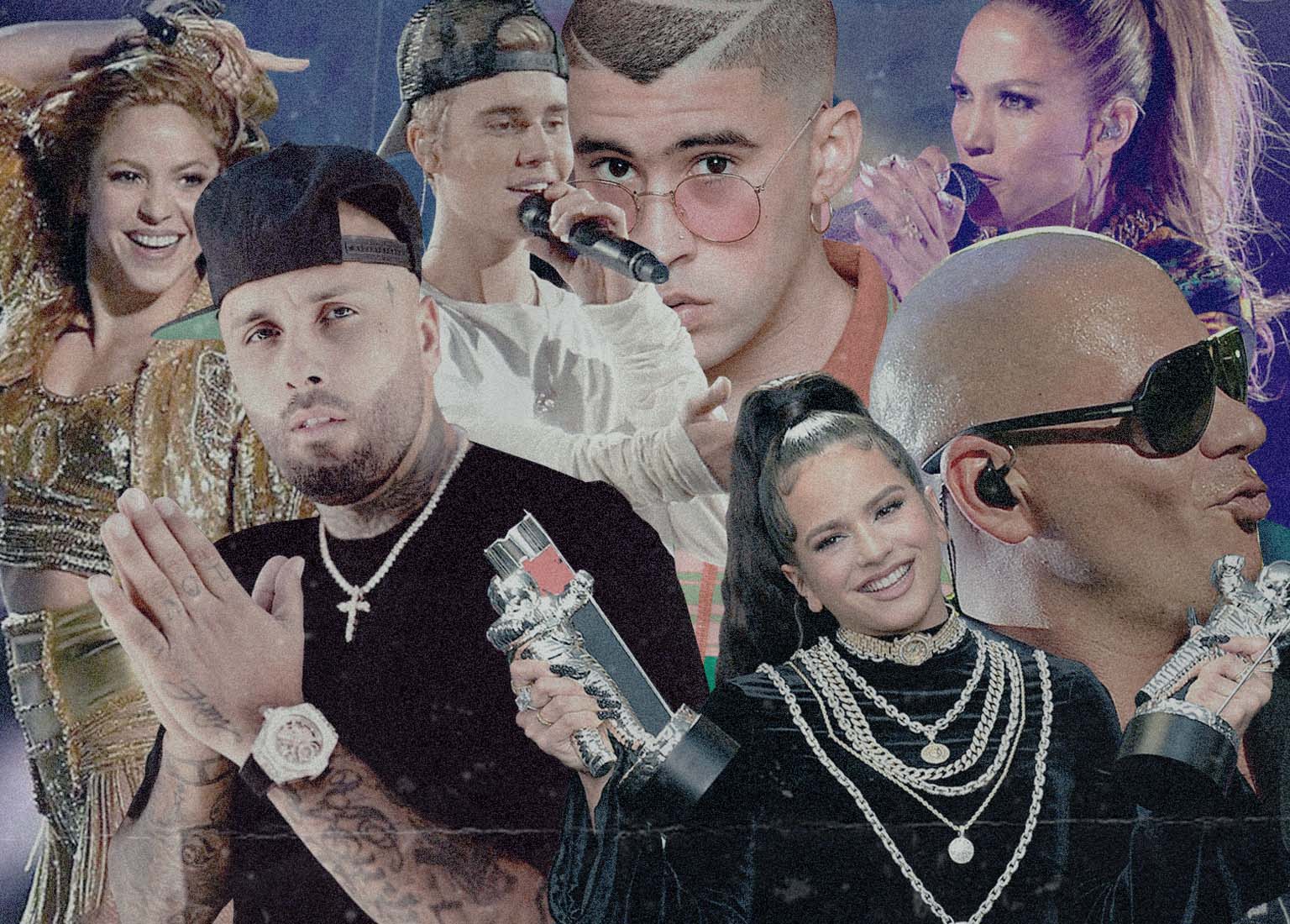

Rosalia. J Balvin. Nicky Jam. Bad Bunny. Names that have come to grace our headphones and speakers recently in a way that was not common before. Until the drop of “Despacito” by Luis Fonsi and Justin Bieber, the representatives of Spanish language music were J. Lo, Shakira, and Pitbull.

Yet, in the past year Spanish language music has been on the rise in popularity, increasing in Spotify plays and YouTube views. In fact, Billboard finds that there were “34.7 billion video streams of Latin music in 2017, and 44.5 billion streams in 2018, marking 28.2 percent growth year-over-year. That accounts for 18.4 percent of the total video streaming marketplace.” The globalization of the music, the resurgence of reggaetón, and the infusion of Spanish language into pop songs has unleashed a wave of infatuation for the genre. A genre that the majority of its listeners probably cannot understand. In a 2018 article from Billboard, “danceability” is cited as the cause for the sudden popularity wave. This quality supersedes what many would otherwise notice in their music of choice, such as lyrical content. The songs are fun, and without the obligation to know or understand the lyrics, they can simply be for enjoyment of the instrumentals and the signature upbeat percussion and bass. Yet, this rise is not so simple.

Many of the most popular Latin tracks feature another artist who is already popular in mainstream pop music, such as Justin Bieber on “Despacito” or Cardi B on “I Like It” by Bad Bunny. The style of collaboration and sampling call to mind other genres like hip-hop and rap, which utilize sampling, features, and collaboration as a focal point in musical style and composition. The introduction of Spanish language music into mainstream culture is exciting, in that a new style that is not in English is becoming globalized. No longer does the most international or most popular song have to exist in English for it to be enjoyable or gain clout. If the quality of the music itself can be priority, then any song in any language has a shot, because the lyrics do not need to be understood. Further, it’s a step away from the bastardization of non-white-centric cultures and adds diversity to the musical canon. After all, “Despacito” was tied for longest running number one song on the Hot 100 chart until “Old Town Road” took the title earlier this year.

Additionally, the rise of streaming services also creates a more accessible platform for the genre. No longer do people have to go into a store and physically buy an album. In many ways, this access is great. It’s cheaper and easier and allows more people to hear more music. Audiences can pick their favorite songs from Spotify or Apple Music that cater to their usual sound.

In this context though, this selection is a filtering of the *most* English/American-pop-sounding Spanish songs that cater to the American audience. It’s particularly distressing when the U.S. also happens to be such a large export for music and major media industries, creating minimal, small gateways for any artists or individuals (american ones? or do you mean any artists from other countries?) to gain global, or even prominent, success. In all this success, however, the rise in popularity of this genre is not so simple or wholly innocent.

While music should be more diverse and more accessible to people of other cultures, the line can often be crossed by consumers and producers alike into the dangers of cultural appropriation. Examples of this phenomena include Drake, who is problematic for a plethora of reasons, on “Mia” with Bad Bunny, where he adopts a “soy papi” persona to cater to an audience that views speaking Spanish as attractive while rejecting the culture or the people to whom the language belongs. Other artists from Jason Derulo to Drake Bell have done the same, using the trendiness of the language and reggaeton style to elevate their fame while giving minimal effort to otherwise understand the culture.

The exploitation is worse when you realize that often these stars don’t speak Spanish — a at all — and have simply learned the basic phrases or lyrics for the song only to forget them a month or two after release. Important to note too is the very specific subset of Spanish language music that is being popularized — reggaeton and trap — meaning that other styles, classic styles that don’t provide the similar tone or beat to other American music, will be left to the wayside. Former major label [(what was his position? major label executive?), Juan Paz, tells Rolling Stone that “when everything becomes a monoculture, it’s dangerous for the sake of artistry.” Some veterans in the music industry are wary of catering towards young people too heavily, like past generations consistently concerned about the next generations tainting tradition. Rolling Stone also mentions that “class and race are likely even deeper fault lines than age.

Much like hip-hop was once derided in the U.S., for much of its existence reggaeton has been looked down on as dangerous music made by poor people — in places like Puerto Rico, it was actively sought out and confiscated by the police.” This claim is true (do you have to say that the claim is true? is it even a claim or just a statement of fact in the first place?) and calls to attention deeper issues in consumption. What happens when the moment has passed, when the style is no longer trendy? Other styles of Spanish music may have been so pushed to the outside that they are unable to make a comeback.

Moreover, another culture will have been reduced to a temporary fad, a money maker until it no longer is fitting for the market. In the same vein, this fetishization and appropriation is apparent not only in terms of consumption but also the production within the genre. The lack of diversity among the most recent and popular faces of Latin and Spanish language music is stark and apparent. By and large, the most famous stars are white or incredibly light-skinned individuals, raising the question of what kind of Spanish and what kind of Spanish speaker is “palatable” or acceptable to the consumer. Moreover, who is the consumer? In the United States at least, where anti-immigrant and racist rhetoric is rampant and for some reason permissible, it’s hard to understand (or really far too easy in the nation known for appropriation) how the Spanish language is great for dancing, is sexy, and white Spaniards are attractive and marketable, but Spanish speakers, who are darker skinned and don’t cater to the nonexistent (why do you say it’s nonexistent?) image we’ve conjured for the ideal Latinx person are literally shoved to the side.

The line to walk here is tricky, especially when trying to understand how to be a responsible consumer. The fact of the matter is that Spanish language music is popular, and its popularity is beautiful and wonderful and adds variety to the generic white pop that normally saturates radio waves. In doing so, however, recall individual positionality (feels a little too essay-ish in this context — could you put it more simply?) in the digestion of this music, whether you support Spanish speakers (especially non-white Latinx people) as much as you support the music derived from a traditionally dismissed culture. Complicate (is this the right word here? maybe examine?) which Spanish speaking artists you listen to and if they also participate in the active fetishization and exploitation. Push back on artists, even your faves, when they do questionable moves.

Yet, in the past year Spanish language music has been on the rise in popularity, increasing in Spotify plays and YouTube views. In fact, Billboard finds that there were “34.7 billion video streams of Latin music in 2017, and 44.5 billion streams in 2018, marking 28.2 percent growth year-over-year. That accounts for 18.4 percent of the total video streaming marketplace.” The globalization of the music, the resurgence of reggaetón, and the infusion of Spanish language into pop songs has unleashed a wave of infatuation for the genre. A genre that the majority of its listeners probably cannot understand. In a 2018 article from Billboard, “danceability” is cited as the cause for the sudden popularity wave. This quality supersedes what many would otherwise notice in their music of choice, such as lyrical content. The songs are fun, and without the obligation to know or understand the lyrics, they can simply be for enjoyment of the instrumentals and the signature upbeat percussion and bass. Yet, this rise is not so simple.

Many of the most popular Latin tracks feature another artist who is already popular in mainstream pop music, such as Justin Bieber on “Despacito” or Cardi B on “I Like It” by Bad Bunny. The style of collaboration and sampling call to mind other genres like hip-hop and rap, which utilize sampling, features, and collaboration as a focal point in musical style and composition. The introduction of Spanish language music into mainstream culture is exciting, in that a new style that is not in English is becoming globalized. No longer does the most international or most popular song have to exist in English for it to be enjoyable or gain clout. If the quality of the music itself can be priority, then any song in any language has a shot, because the lyrics do not need to be understood. Further, it’s a step away from the bastardization of non-white-centric cultures and adds diversity to the musical canon. After all, “Despacito” was tied for longest running number one song on the Hot 100 chart until “Old Town Road” took the title earlier this year.

Additionally, the rise of streaming services also creates a more accessible platform for the genre. No longer do people have to go into a store and physically buy an album. In many ways, this access is great. It’s cheaper and easier and allows more people to hear more music. Audiences can pick their favorite songs from Spotify or Apple Music that cater to their usual sound.

In this context though, this selection is a filtering of the *most* English/American-pop-sounding Spanish songs that cater to the American audience. It’s particularly distressing when the U.S. also happens to be such a large export for music and major media industries, creating minimal, small gateways for any artists or individuals (american ones? or do you mean any artists from other countries?) to gain global, or even prominent, success. In all this success, however, the rise in popularity of this genre is not so simple or wholly innocent.

While music should be more diverse and more accessible to people of other cultures, the line can often be crossed by consumers and producers alike into the dangers of cultural appropriation. Examples of this phenomena include Drake, who is problematic for a plethora of reasons, on “Mia” with Bad Bunny, where he adopts a “soy papi” persona to cater to an audience that views speaking Spanish as attractive while rejecting the culture or the people to whom the language belongs. Other artists from Jason Derulo to Drake Bell have done the same, using the trendiness of the language and reggaeton style to elevate their fame while giving minimal effort to otherwise understand the culture.

The exploitation is worse when you realize that often these stars don’t speak Spanish — a at all — and have simply learned the basic phrases or lyrics for the song only to forget them a month or two after release. Important to note too is the very specific subset of Spanish language music that is being popularized — reggaeton and trap — meaning that other styles, classic styles that don’t provide the similar tone or beat to other American music, will be left to the wayside. Former major label [(what was his position? major label executive?), Juan Paz, tells Rolling Stone that “when everything becomes a monoculture, it’s dangerous for the sake of artistry.” Some veterans in the music industry are wary of catering towards young people too heavily, like past generations consistently concerned about the next generations tainting tradition. Rolling Stone also mentions that “class and race are likely even deeper fault lines than age.

Much like hip-hop was once derided in the U.S., for much of its existence reggaeton has been looked down on as dangerous music made by poor people — in places like Puerto Rico, it was actively sought out and confiscated by the police.” This claim is true (do you have to say that the claim is true? is it even a claim or just a statement of fact in the first place?) and calls to attention deeper issues in consumption. What happens when the moment has passed, when the style is no longer trendy? Other styles of Spanish music may have been so pushed to the outside that they are unable to make a comeback.

Moreover, another culture will have been reduced to a temporary fad, a money maker until it no longer is fitting for the market. In the same vein, this fetishization and appropriation is apparent not only in terms of consumption but also the production within the genre. The lack of diversity among the most recent and popular faces of Latin and Spanish language music is stark and apparent. By and large, the most famous stars are white or incredibly light-skinned individuals, raising the question of what kind of Spanish and what kind of Spanish speaker is “palatable” or acceptable to the consumer. Moreover, who is the consumer? In the United States at least, where anti-immigrant and racist rhetoric is rampant and for some reason permissible, it’s hard to understand (or really far too easy in the nation known for appropriation) how the Spanish language is great for dancing, is sexy, and white Spaniards are attractive and marketable, but Spanish speakers, who are darker skinned and don’t cater to the nonexistent (why do you say it’s nonexistent?) image we’ve conjured for the ideal Latinx person are literally shoved to the side.

The line to walk here is tricky, especially when trying to understand how to be a responsible consumer. The fact of the matter is that Spanish language music is popular, and its popularity is beautiful and wonderful and adds variety to the generic white pop that normally saturates radio waves. In doing so, however, recall individual positionality (feels a little too essay-ish in this context — could you put it more simply?) in the digestion of this music, whether you support Spanish speakers (especially non-white Latinx people) as much as you support the music derived from a traditionally dismissed culture. Complicate (is this the right word here? maybe examine?) which Spanish speaking artists you listen to and if they also participate in the active fetishization and exploitation. Push back on artists, even your faves, when they do questionable moves.