Cocteau Twins, Young Thug,

and the Incoherent Beauty of Life

Words: Asher White

August 10 2021

Resisting the urge to decode...

“I remember being so fucking high on this song… like, my mouth—I couldn’t even open my fucking mouth,” laughs Future. “… but when I listened to it back the next day, I was like… what was I saying? But I loves it, like, this shit sounds raw though. I’m not gonna change it.”

He made the right choice, and the outrageous success of “Tony Montana” is a testament to this instinct. The hook in question—a slurred, halting pronunciation of the Scarface protagonist’s name—is captivating, the type of instantly memorable chant that gets co-opted by frat houses and screamed from the backseat of a car. It holds an unplaceable sentiment that could plausibly be anguish, fatigue, ecstasy, or determination. In Future’s mouth, the name becomes a strange mantra—mysterious, borderline nonsensical, and oddly triumphant. Future explains to Rosenberg, “I know there’s a little something that you can’t really understand, but it’s that that makes you feel like you like it. That’s what you like it from.”

Future seems somewhat surprised at the single’s success and amused by its origin. But the shrewdness of his analysis—that the song’s weird, garbled hook is exactly the quality that makes it compelling—suggests that he is not just a master of his own craft but a prophet of rap at large. Over the next few years, Future’s music would take stranger and more ambiguous shapes—his 2017 album HNDRXX is wrapped in a thick fog and prone to ghostly, beatless expanses—and his peers and acolytes would push the form even further.

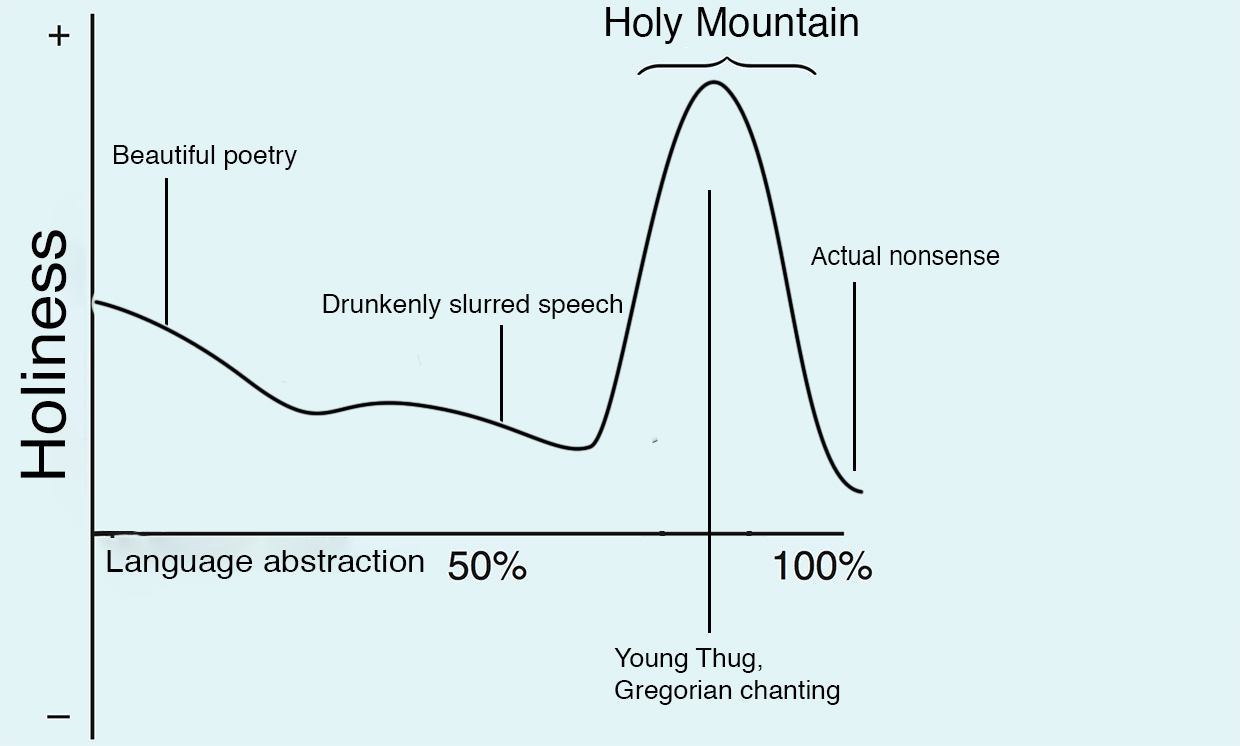

Young Thug had a “Tony Montana” of his own with “Lifestyle,” an exuberant 2014 single for Atlanta collective Rich Gang. The pleasures of “Lifestyle” are similarly immediate and undeniable, the first hint that Young Thug would possess one of the most expressive voices in popular music. He’s the one of the only rappers who will reliably jump a full octave to repeat a hook (as he first does on 2013’s “Dead for Real”); who is so confident in his technical ability that he can abandon precision altogether for pure, freeform expression (as he does in the second half of “Givincey,” maybe his finest hour). His chaotic sense of melody leads him to erupt into hooks mid-verse (what Charley Locke calls “emotional onomatopoeia”); singles like “Flava” and “Stoner” are basically 4-minute sequences of choruses strung together. But “Lifestyle” put him on the map. Its chorus is a squealed stream of glee—the type of acrobatic vocal run that would come to define his work. Its unintelligible passion immediately went viral, spawning an entire genre of content: thinkpieces and YouTube videos daring civilians to decipher Young Thug’s lyrics, linguists deconstructing his vocal techniques. The inscrutable joy of Young Thug—and the uncertainty of what he was actually trying to say—was thrilling. It seemed that what gave the song such endless replay value was the sense that there was always more to discover—that contained within “Lifestyle” was a dictionary of emotion that transcended language.

A google search of “cocteau twins meme” returns hundreds of variations on the same theme: that dream-pop band Cocteau Twin’s lyrics are unintelligible, and also go really fucking hard. As long as their music has existed, Elizabeth Fraser’s vocal technique has fascinated and perplexed listeners.1 Critics have attempted to pin it down: a 1993 profile by Jason Morgan and Diana Trimble describes Fraser’s voice as infantile (“The intimate conversations of pure emotion held before the acquisition of language. The lullaby. Lallation. The imitative sounds a child makes in the effort to infuse language with meaning”) before pivoting to invoke Dadaism (“Dada freed words from their definitions by rearing new words with flexible definitions... It can mean whatever you want... Penetrating the private language is half the fun”); a piece from 2019 borrows the term glossolalia, or speaking in tongues. During their initial rise to fame, it was inevitably asked in every interview Cocteau Twins did: what do the lyrics mean?

The band’s official website has a page dedicated to Fraser’s various answers, and somewhat cryptically, these explanations vary over the years, possibly as her approach changed. At times, she was allegedly crafting vocabularies of her own from books of archaic languages she didn’t understand; elsewhere, she indicated her lyrics had concrete meanings but were obscured by her diction; or that maybe she used her diction in order to intentionally obscure the meaning as “a coping skill”; she once described herself as “just feeling into a fucking microphone,” and that same year she offered, “I’ve got reams and reams of words that I don’t have a clue what they mean, but I wanted them because, I knew I’d be able to express myself without giving anything away.”

Ultimately, the origin of her lyrics doesn’t really matter. The result is the same: sounds that threaten to congeal into words but never quite become clear, intermittent shards of language that glint in and out of focus. Her approach keeps language perilously on the edge of abstraction, lending the songs an eerie, unstable sense of familiarity, like searching for a signal on an old radio. There is an undeniable, almost urgent sense of meaning, but it’s always just beyond reach.

The abundance of Cocteau Twins memes and their consistent premise (sobbing in your bedroom to indecipherable, Scottish gibberish) indicates that the vast majority of listeners are not deterred by their inscrutability—in fact, they’re captivated by it. As Future proposes, it’s the reason they listen. The prevailing sense is that there’s something more beyond comprehension, something off-limits in Cocteau Twins’s music (it is telling that the title of their most successful album, Heaven or Las Vegas, posits a choice between two destinations that both often represent promise without fulfillment). As Fraser puts it, “Fortunately [the nonsensical words] come out making a sort of sense. They make enough sense to other people for them to actually… they can understand, they can see things, they have these mental pictures… [Fans’] interpretations are so beautiful that sometimes I have preferred what they have written to what I actually sang, it has been much more eloquent.”

Linguist Darin Flynn echoes this comment in his analysis of Young Thug: "It's almost like a Rorschach ink blot test. In a way, what Young Thug originally meant becomes less interesting than your own interaction with and interpretation of his music, which depends entirely on who you are.

The practice of creating deliberately-unreadable text existed long before it was retroactively deemed “asemic writing” by visual poets Tim Gaze and Jim Leftwich. What does it mean to write words in a language that doesn’t exist at all? Or to distort characters to the point of abstraction?

Peter Schwenger’s 2019 book Asemic: The Art of Writing explores an approach to writing taken from Brazilian philosopher Vilém Flusser: “to strip the marks before us of their habitual significance so that they appear before us strange—and often strangely beautiful.”2

Asemic: The Art of Writing advocates for this: a radical, deconstructive approach to language. The result is text (or something like that) that doesn’t contain meaning but evokes it. It surveys artists and writers who make work that resists direct readings in order to maintain a sense of constant discovery: writing that is never decoded has eternal possibilities! By comparison, writing that has a clear, innate meaning can lose a spiritual quality—as Schwenger quotes Roland Barthes: “for writing to be manifest in its truth, it must be illegible.”

Schwenger suggests that when we attempt precise articulation, we may gain logic, but what we lose are the “embryonic tendencies of the mind.”3 He explains:

“Asemic writing conveys something of that elusive nonverbal element… by foregrounding the materiality of words. Through abstract linear gestures on the page, it evokes interior ones— mental movements and shapes, tendencies and qualities. The weaving together of these produces a texture, the texture of something that precedes thought and language. Asemic writing, so resolutely noncommunicative, can nevertheless communicate this mental texture to us, even if it does so in a language beyond words.”

In Empire of Signs, Roland Barthes dreams of an encounter with a foreign language, unmarred by the baggage of the West:

“The dream: to know a foreign (alien) language and yet not to understand it… to know, positively refracted in a new language, the impossibilities of our own; to learn the systematics of the inconceivable; to undo our own “reality” under the effect of other formulations… in a word, to descend into the untranslatable, to experience its shock without ever muffling it...”

Barthes’ fantasy to “perceive a landscape which our speech could under no circumstances either discover or divine” is, itself, uniquely Western—totally lustful for exotic bliss—but also borne of a frustration with the West’s insatiable appetite to conquer and catalog. He later writes resonantly on the relinquishing of awareness that occurs in an unfamiliar country, on the blissful ignorance of not knowing the language spoken around you:“The murmuring mass of an unknown language constitutes a delicious protection, envelops the foreigner (provided the country is not hostile to him) in an auditory film which halts at his ears all the alienations of the mother tongue: the regional and social origins of whoever is speaking, his degree of culture, of intelligence, of taste, the image by which he constitutes himself as a person and which he asks you to recognize. Hence, in foreign countries, what a respite! Here I am protected against stupidity, vulgarity, vanity, worldliness, nationality, normality. The unknown language… the emotive aeration, the pure significance, forms around me, as I move, a faint vertigo, sweeping me into its artificial emptiness, which is consummated only for me: I live in the interstice, delivered from any fulfilled meaning.”5

This is the ecstatic experience of becoming lost, of giving oneself to the promise of the unknown. It predicts the urge to create asemic writing, to generate illegible text in which one can infinitely seek and project one’s own meaning onto.But our fascination with the unknown goes deeper, and lies at the core of mystic practices from Judaism to Sufism. Across ancient religious practices, it seems that the most consistent advice is to accept and internalize what cannot be understood. From 13th-century Persian poet Rumi:

“The body itself is a screen

to shield and partially reveal

the light that’s blazing

inside your presence.

Water, stories, the body,

all the things we do, are mediums

that hide and show what’s hidden.

Study them,

and enjoy this being washed

with a secret we sometimes know,

and then not.”6

“Spiritual awareness is born of encounters with the mystery. It begins with an almost trivial passing astonishment at the irreducible paradox that underlies everything… This is the mystery. That all the important moments, and probably at the source of all moments there is something that is illogical, paradoxical, and sort of impossible. Male and Female. Good and Bad. Loved and Hated. Sought and Shunned. Alive and Dead. A time for loving and a time for hating. Unfortunately, it is usually the same time.”7

The mystic receives insights from a source that is “deeper” or “higher” than the ordinary human mind. But how can those insights be conveyed? Language, whether spoken or written, is our ordinary vehicle of communication, itself a product of the mind and one that shares the limitations of its source. In order to communicate a translinguistic or “ineffable” level of insight, the mystic needs to struggle against the barriers of language, perhaps by stretching the ordinary discursive vehicle to new poetic heights, perhaps by discovering within language a previously untapped symbolic stratum, perhaps by speaking in a holier tongue, by resource to some code, or else by bearing witness to the utter breakdown of language through such phenomena as glossolalia, sacred stammer, or the glorification of silence.9

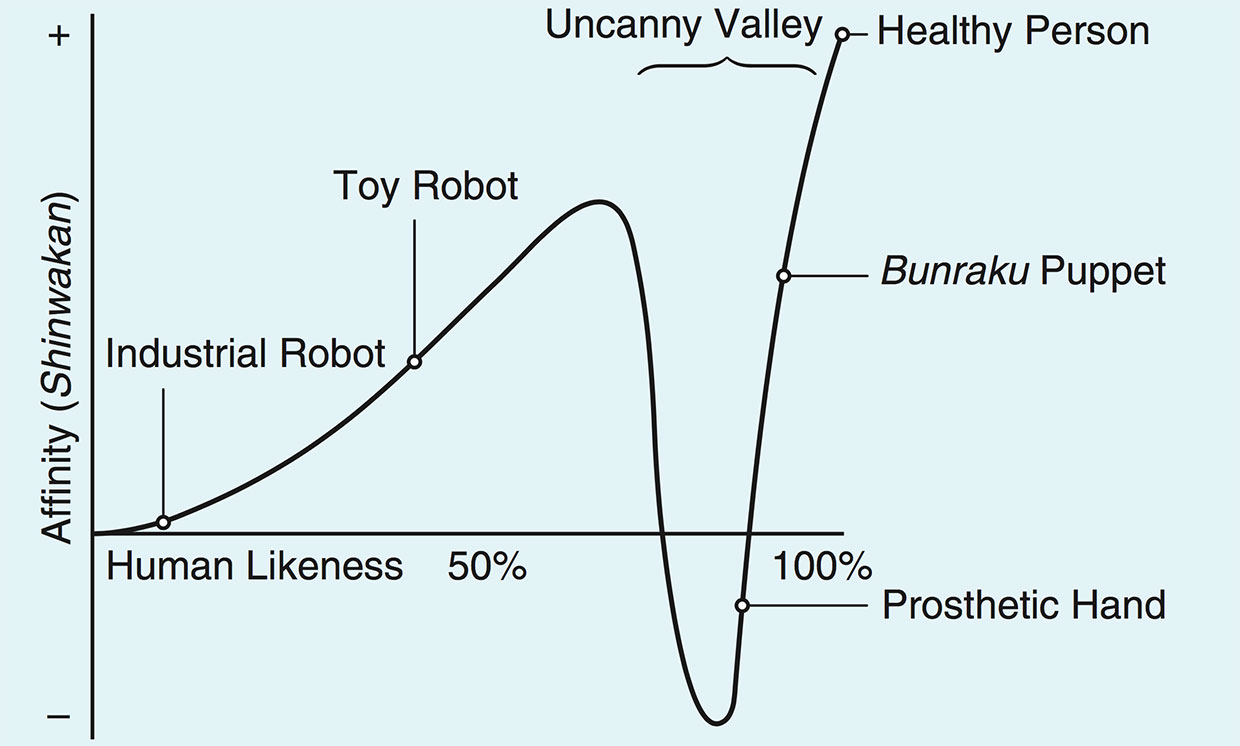

Encounters with these deconstructions lead us to believe we are engaging with the sublime; because the sublime is always concealed and never fully understood, it is the appearance of the opaque that promises us the presence of the sublime. An obstruction in our view indicates there is presently something worthy of being obstructed, or something that can only be accessed through a process of obstruction. Encounters with this opacity or ambiguity in otherwise direct forms of communication (like rap music) gesture to something beyond the form.But there’s a delicate balance, as Schwenger reminds us in Asemic: “asemic writing is assigned meaning by convention and habit; it does this by graphic configurations alone.”10 Crucially, the form never gives into complete abstraction— an imminent sense of readability must be preserved (if never rewarded). There’s always an aching potential to comprehend the esoteric hymns of Elizabeth Fraser, or the unspeakable ecstasy in Young Thug’s wails, or the dread in Future’s chanting. This type of quasi-abstract art generates a fog of mysticism that allows us to project what we’d like to see while still providing us with discernable substance.

2Schwenger, Peter. Asemic: The Art of Writing. Minneapolis, University Of Minnesota Press, 2019, p. 5. Orginally from Flusser:

“Writing becomes almost mysterious, if we discover it by deliberate consideration. If we draw off the cover of habit… which renders writing an obvious gesture, taken at face value, it becomes a gesture of such complexity that it defies description.”

3What French writer Nathalie Sarraute termed tropisms:

“These movements, of which we are hardly cognizant, slip through us on the frontiers of our consciousness in the form of undefinable, extremely rapid sensations. They hide behind our gestures, beneath the words we speak, the feelings we manifest, are aware of experiencing, and are able to define… While we are performing them, no words express them, not even those of interior monologue.”

4Schwenger, 104.

5Barthes, Roland, and Richard Howard. Empire of Signs. New York, NY Hill And Wang, 2009, p. 9.

6Rumi. The Essential Rumi. Translated by Coleman Barks, New York, Castle Books, 1995, p. 172.

7Kushner, Lawrence. Honey from the Rock: Visions of Jewish Mystical Renewal. San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1977, pp. 34–35.

8Green, Arthur. A Guide to the Zohar. Stanford, Calif., Stanford University Press, 2004, p. 7.

9Green, 8 - 9.

10Schwenger, 109.

11If one were to map this directly onto Jewish mysticism, the cut-and-dry Old Testament would fall near the moderately-holy, highly-legible first quarter, and the esoteric, somewhat impenetrable Zohar would fall towards the deeply-holy, highly-illegible third quarter.